This year’s iPhone announcements were special for me because it is the first time since 2017 that I know I will be buying a new phone. My partner’s 6S has some sort of circuit fault that discharges batteries extremely quickly, so she will be getting my iPhone X — and I will be getting, well, something announced today. But it is not easy because, more than ever, it feels like there is some compromise at every level. That is not a criticism, only an observation based on my priorities.

But we will get to that.

The Event Itself

I do not wish to make light of this harrowing pandemic, but the more I see Apple’s new presentation format, the more I like it. The nostalgic soul in me pines for the Stevenote era because he was one of the best public speakers in modern corporate history. Yet, one of the drawbacks of a golden era Steve Jobs keynote — from, say, 2005 through 2008 or so — is that it maximized Jobs’ presence at the expense of the thousands of people involved in creating a product or service. Sure, you would occasionally hear from Phil Schiller, Jony Ive, Scott Forstall, and others, but there was a gravity around Jobs that made it hard for others to get as much attention.

The Tim Cook era Apple has distributed presentations amongst greater numbers of executives, managers, and marketing types, but I do not think it has ever been as effective as it is in the videos they have been forced to create as a result of this pandemic. We get to hear from even more people who were involved in creating these products — and likely more than a live theatrical production could handle. There are logistical reasons for not handing off the presenter role every few minutes in a live setting, and there are also many people who simply are not comfortable in a live broadcast setting with an audience.

As many observers have pointed out, it is also a far more diverse group of presenters. Apple really does pick presenters who are intimately familiar with a technology because they worked on it. I am enjoying hearing more from these voices in addition to the usual suspects on the executive team.

Today’s presentation did have its lulls. The iPhone 12 lineup supports 5G — more on that in a minute — so not only did Apple explain at multiple points how revolutionary 5G is supposed to be, an executive from Verizon appeared to help explain how revolutionary 5G is supposed to be with the help of Verizon. There was also a demo of a new iPhone version of “League of Legends”, so we really hit the Apple keynote jackpot today.

I wonder what Verizon did to deserve such prominent placement during today’s keynote. It has been a very long time since Apple has donated several minutes of valuable iPhone-adjacent air space to a carrier, or a technical partner of any kind. But, like the September keynote, this stream clocked in at a few minutes over one hour long, so it isn’t like those moments pushed live audiences to some kind of bladder breaking point.

5G

As I have written for years now, the way 5G is being sold to the public is wildly disproportionate to the actual day-to-day impact it will have on most of us most of the time. At the moment, 5G is largely a useful buzzword for when you want billions of dollars in tax breaks, a shortcut for newspapers to seem more technologically advanced, and a way to eat up phone batteries at speeds slower than LTE.

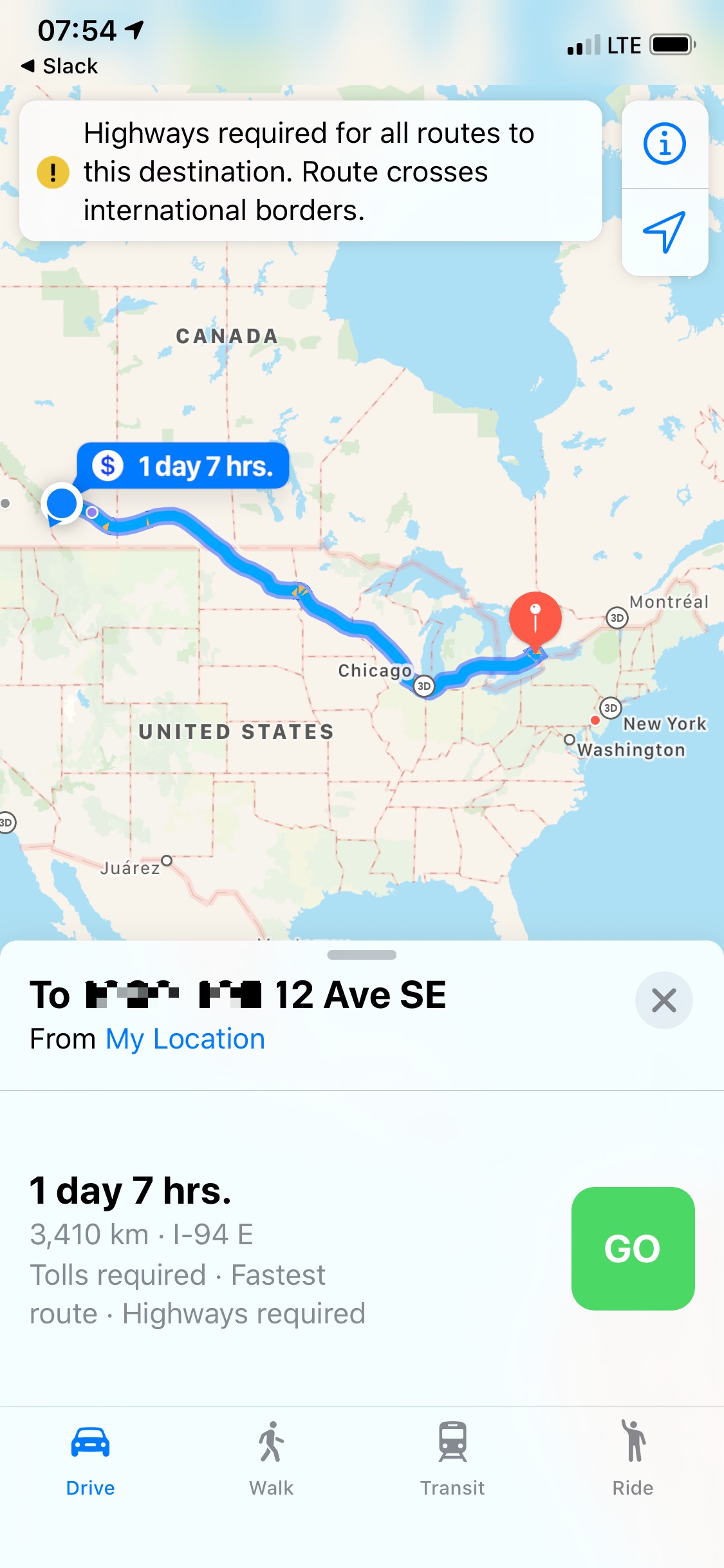

But that surely does not have to be the case. One reason speeds are so slow right now is because faster 5G waves require users to be in closer proximity to cell towers and, so far, the infrastructure coverage is weaker than for LTE in the United States. But what if a company starts shipping a whole bunch of the most popular smartphone model in that country? That may spur a wave of adoption that effectively requires cell carriers to build out infrastructure more quickly. Outside of the U.S. and with many different 5G frequencies used worldwide, the situation surely differs. I am interested to know what it is like in Calgary, for example. When Apple gets behind a technology, though, it tends to push the industry as a whole.

5G radios also require more power, but Apple is being clever there as well. The iPhone 12 models are usually using LTE but will ramp up to 5G when it is necessary. That seems like an adept way to balance speed and battery life.

But, oh boy, did Apple sell 5G hard during today’s presentation, to points where I think they overstepped.

For example, before either iPhone was unveiled, Tim Cook spoke generally about 5G. One of the things that caught my ear was his claim that it “helps protect your privacy and security” because it is so fast that you are less likely to connect to insecure public Wi-Fi hotspots. There is some truth to that statement, but it sounds an awful lot like spin. Public Wi-Fi, at least where I am, is often slower than LTE, so it isn’t a compromise of privacy for speed. A Wi-Fi hotspot is appealing because carriers in many countries have monthly data allowances on their plans, so connecting to Wi-Fi avoids expensive overage charges.1

Then, during the introduction of the iPhone 12 Pro, Greg Joswiak said that doctors will be able to download scans faster, and implied that 5G could make the difference between life and death. This is probably true in some circumstances, but it is a wild claim to drop during an iPhone keynote. There are many cases where having faster network speeds is simply a nicer and better experience for most customers, and I found the dive into a possible life-saving realm of 5G to be more distracting than convincing.

The iPhone 12 and iPhone 12 Pro Lineups

The thing that is hard about this year’s iPhone lineup is that they are hard to choose between for both the ways that they overlap and the ways that they differ.

The best news this year, from a basic hardware standpoint, is that Apple has resurrected the iPhone 5-like flat sided form factor and mixed it with the glass sandwich of the iPhone 4 and recent iPhone models. That hardware design language has always been my favourite for its in-hand stability and precision, and I am glad to see it brought back and modernized. It is basically the same design across the lineup, with the iPhone 12 getting an aluminum chassis and the Pro models sporting stainless steel.

The processor is also the pitched as being the same on all models — though benchmarking experts will tell us the extent to which they are equivalent. They all have the same Ceramic Shield cover glass, which, Apple says improves the likelihood it will survive a drop by four times, they all have OLED displays, they all have MagSafe — another blast from the past — and they all support 5G. These phones are, in many ways, the same.

As I wrote above, I am upgrading from an iPhone X, so there is a lot that will be new to me and I am not a great resource for year-over-year comparisons. But I do know what I like and use on this phone. I prefer a smaller form factor, so the iPhone 12 Mini caught my attention in a big way. But, though I am excited by the prospects of a wide angle lens, I use the telephoto lens on my current iPhone to know that I do not want to be without it. The telephoto is only available on the Pro models, so I will naturally be guided to them.

But there’s a big catch here, which is that the cameras in the iPhone 12 Pro Max are no longer consistent with those in the smaller Pro model. Across the lineup, most of the camera changes this year seem to be in software rather than lenses or sensors. The situation is not so simple with the Pro Max, as Sebastiaan de With explains:

In addition to a better lens, the 12 Pro Max has the room to pack a new, 47% larger sensor. That means bigger pixels, and bigger pixels that capture more light simply means better photos. More detail in the day, more light at night. That combines with the lens to result in almost twice as much light captured: Apple claims an 87% improvement in light capture from the 11 Pro. That’s huge.

But that’s not its only trick: the 12 Pro Max’s Wide system also gets a new sensor-shift OIS system. OIS, or Optical Image Stabilization, lets your iPhone move the camera around a bit to compensate for your decidedly unsteady human trembly hands. That results in smoother video captures and sharp shots at night, when the iPhone has to take in light over a longer amount of time.

These appear to be big improvements to the camera and they are, frustratingly, only on the biggest iPhone model. That makes complete sense from an engineering perspective and I do not think Apple should restrict the camera of the bigger model because it no longer has parity with its smaller sibling.

But, damn, that makes this a pretty difficult choice. If I want the best camera on an iPhone this year, I have to live with a size I find harder to use day-to-day; if I want to get the size that works best for me, I have to sacrifice a camera mode I use most. But, as choices go, I could just stick with the middle-ground option.2 That seems like a sensible compromise all around, but I do hope that sensor-based stabilization system comes to smaller iPhones by the time I am ready to buy another.