Apple has long been a company of measured progress, but for two years in a row, they’ve delivered a substantial leap in the abilities and extensibility of iOS. iOS 7 brought a complete top-to-bottom redesign, while iOS 8 allowed developers to interact with the OS and other apps more than they ever could previously.

But leaps and bounds of supersized progress don’t come for free; indeed, both releases felt like they lacked the kind of software quality we’ve come to expect from Apple. While I can’t think of a single product they’ve made that didn’t have any bugs, the severity and regularity of quality-assurance gaps made the past two years of iOS feel rushed and a little incomplete.

Apple has faced this before; Mac OS X Leopard, released in 2007, was riddled with far more bugs and quality issues than its predecessor. Its 2008 successor, dubbed Snow Leopard, was famously billed as having “no new features” — that wasn’t entirely accurate, but it was the thrust of the release: bug fixes, bug fixes, and bug fixes (and Exchange support).

iOS 9 is an attempt to strike the balance between these extremes. There are two sets of promises: it’s supposed to fix a lot of bugs and improve overall performance and stability, but it’s also supposed to be a fully-featured release. So, is it?

I’ve been using iOS 9 since early June on my iPhone 5S and iPad Mini 2. This is what I’ve learned.

Contents

- Compatibility

- Installation

- Under the Hood

- UI

- Springboard

- iPad

- Keyboard

- Searching Harder

- Safari

- News

- Notes

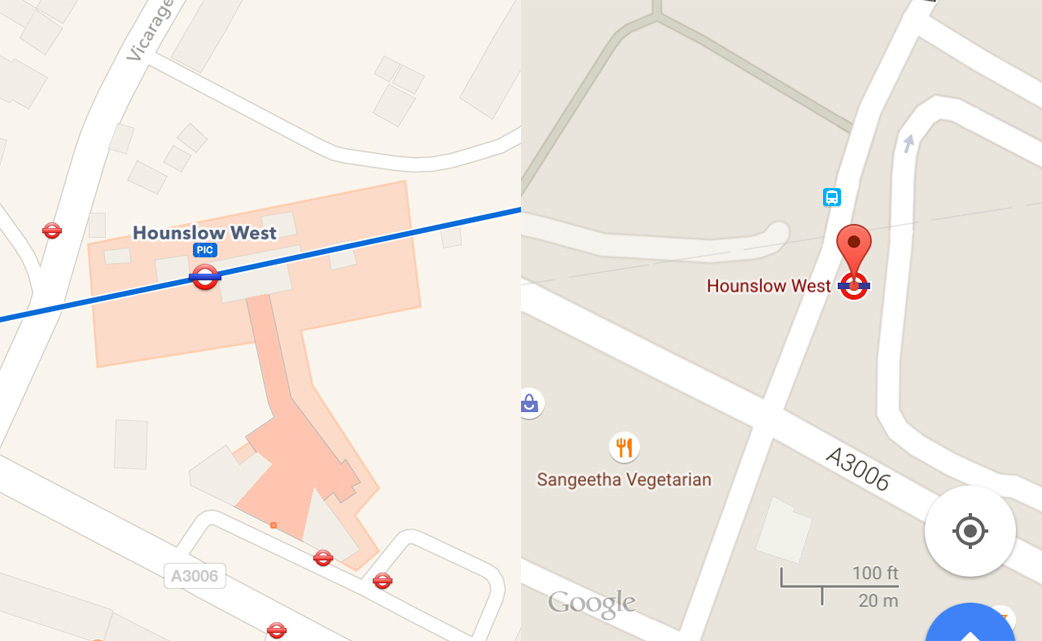

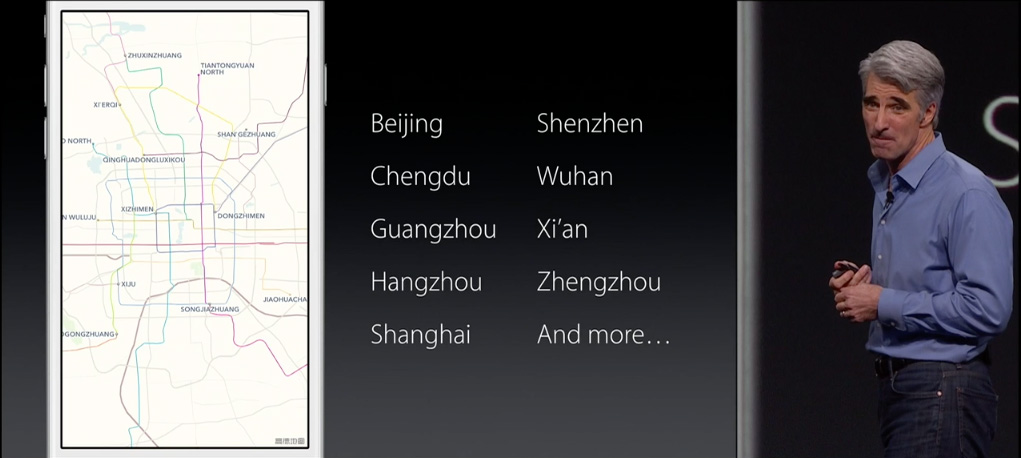

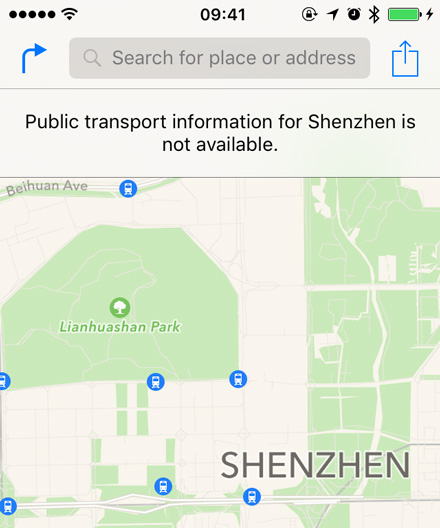

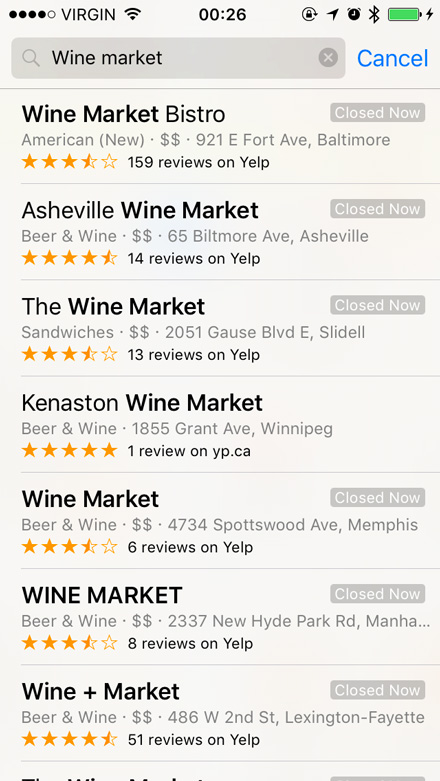

- Maps

- Grab Bag

- Recommendations and Conclusions

Compatibility

Impressively, iOS 9 runs on all the same devices as iOS 8 did. If you have an iPhone 4S or iPad 2 or newer, or an iPod Touch with a 4-inch display, you can update to the latest and greatest operating system. Four years is a long time in the smartphone world, but Apple remains just as committed as ever to older hardware.

But, though no devices have been dropped from the compatibility list with this release, there’s also an array of caveats and limitations, as usual. A5 hardware does not support Proactive features, for example. Similarly, only A7-and-newer iPads support picture-in-picture or Slide Over, while only the iPad Air 2 currently supports split-screen multitasking.

But, though the newest features are limited to the most recent hardware, older models should perform far better under iOS 9 than under 8. The iPad 2 is four and a half years old, yet Apple is still dedicating engineering resources to making sure it continues to feel like new hardware. That’s pretty impressive, and it seems to acknowledge a longer upgrade cycle more typical of a computer than, say, a phone.

Installation

Installing iOS 9 is as simple as you’d like and are used to: it’s available both over-the-air, and as a full standalone download. Depending on what device you’ve got, the complete package size will vary from about 1.4 GB for an iPad 2 to over 2.1 GB for an iPhone 6 Plus.

Over-the-air is another story. While there is no single reason why iOS 8’s upgrade rate was noticeably slower than iOS 7’s, the large amount of required disk space — four or five gigabytes — is likely a significant contributing factor, especially considering the amount of 16 GB devices still in use (and, inexplicably, being sold). Apple promises that devices only require about a gigabyte of free space to upgrade to iOS 9.

Updates get even better after you’re running iOS 9 in terms of both timing and available space requirements. Let’s start with the first one by taking a peek at the over-the-air update feed (large file warning). When you run an OTA update, it checks what version of iOS you’re currently on, which version is the latest available, and downloads just the required files for your device. Here’s what that looks like, in part, for a version of iOS 8:

<key>OSVersion</key>

<string>8.4.1</string>

<key>PrerequisiteBuild</key>

<string>12D508</string>

<key>PrerequisiteOSVersion</key>

<string>8.2</string>

<key>SUDocumentationID</key>

<string>iOS841GM</string>

<key>SUProductSystemName</key>

<string>iOS</string>

This is what that looks like for an iOS 9 update:

<key>OSVersion</key>

<string>9.0</string>

<key>PrerequisiteBuild</key>

<string>12H321</string>

<key>PrerequisiteOSVersion</key>

<string>8.4.1</string>

<key>SUDocumentationID</key>

<string>iOS90GM</string>

<key>SUInstallTonightEnabled</key>

<true/>

<key>SUProductSystemName</key>

<string>iOS</string>

Did you catch that? The SUInstallTonightEnabled key is a clue that iOS will now allow you to run system updates overnight or during periods of lower usage. In an increasingly rare moment, the post-PC iOS is learning from the Mac.

If you don’t have enough space on your device for that update, iOS will now offer to delete apps to run the update, then automatically restore them after the update has been completed. It’s a nice touch, but it also seems to acknowledge that 16 GB iPhones are both tiny, yet, here to stay, at least for a while.

Under the Hood

Bitcode, Slicing, and On-Demand Resources, Oh My

Since the release of the iPod Touch in 2007, there have been several distinct versions of iOS created with assets designed or created for specific hardware configurations. An iPhone doesn’t need an iPad’s graphical assets, and the WiFi-only iPod Touch doesn’t need a bunch of cellular-specific code or apps. This is evidenced by the vast chasm between the smallest and largest sizes of iOS 9.

Unfortunately, third-party developers haven’t had a similar ability. After the introduction of the iPad — and, with it, the creation of the universal iOS app format — app sizes grew significantly; this occurred over and over with each introduction of higher-resolution and larger-screened iPhones and iPads. So far, the only solution developers had for this is to create separate iPad and iPhone versions of their app which, due to pressure from both Apple and consumers, is suicidal.

But now there’s a way. Not for supporting developers’ livelihood, sadly, but for them to be able to provide just what’s needed to different devices, at just the right time. Apple calls it “App Thinning”, and it’s comprised of three complementary aspects: bitcode, slicing, and on-demand resources.

Bitcode is kind of cool. Instead of uploading a fully-compiled app, developers can now upload partially-compiled code. Apple can then optimize the app build based on their latest — and, presumably, most efficient — compiler, and the app gets built on the fly.

App slicing requires a little to a lot more work from developers, but probably creates the best balance between space savings and effort required. Developers can now “tag” resources within their app — images, sounds, graphics code, and other data — based on the kind of device they target. For example, neither my iPhone 5S nor my iPad Mini require “@3x” images, which are only used on the iPhone 6(S) Plus, but apps that I download these days often include them and they can take up a lot of space. After a developer correctly tags these files, they will no longer be included in apps that I download to my devices. The same goes for OpenGL vs. Metal, different qualities of audio or video, and different device architectures.

What wasn’t made entirely clear is how sliced apps behave when downloaded from iTunes. It’s easy to figure out how the slicing and building decisions are made when downloading over-the-air from the device, and Apple has built support for slicing into enterprise tools. But the only reference to iTunes comes in the overview document, and there are no specifics:

For iOS apps, sliced apps are supported on the latest iTunes and on devices running iOS 9.0 and later; otherwise, the App Store delivers universal apps to customers.

I haven’t found another reference to how iTunes handles app slicing; for example, when there’s one or multiple devices on a user’s account. Apple PR doesn’t talk to me. (But do they talk to anyone?) I simply don’t know.

Finally, there are on-demand resources. Depending on the app, this might require substantially more work from developers, but it could also provide some of the most significant space savings for users. By storing on the device only the assets that the app needs at the moment and for the foreseeable future, developers can potentially create vastly more depth in their apps without worrying quite as much about a significantly ballooning file size. Furthermore, developers who have already added more depth and size to their apps can strategically make reductions dynamically.

For instance, consider the apps that you’ve downloaded that provide some kind of tour or walkthrough at first launch. As a user, you probably won’t need that again, so the developer can allocate those assets as deletable after use. But the app itself won’t delete them — on-demand assets are entirely managed by the system. That means that one app from one developer could request space currently occupied by another app from a completely different developer. The system is supposed to do the right thing. If there’s an app that you haven’t opened in a long time, it can clear out unneeded assets from that app first, because — let’s face it — you probably won’t notice.

These three things — bitcode, slicing, and on-demand resources — comprise app thinning. Apple’s goals for developers have so far been working in opposite directions: they want developers to build universal apps with Retina-ready graphics and the latest architectures, but they also want to keep the starting capacity of their devices at 16 GB and the free iCloud storage at just 5 GB. Thinned apps work to try to address all of these goals.

I won’t dive into whether this comes close to justify the continued low-capacity devices and services Apple sells by default (it doesn’t) but it certainly reduces the pain of having such a device. If the space savings are as pronounced as Apple says they are — mileage may vary — it will mean a much better user experience for everyone, and less squeeze for those at the base level of device offerings.

Performance

Most years, the newer your iOS device, the less interesting this section will be to you. That perennial rule also usually comes with the unfortunate implication that users with older devices have to deal with increasing obsolescence.

But that’s not the case this year — iOS 9 comes with performance improvements for both new and old devices. Devices that support Metal — Apple’s near-hardware graphics layer — can take advantage of its significantly improved performance in most of the default apps.

For older devices — particularly those of the A5 generation — Apple promises significantly better performance. I don’t have one of those devices any more so I wasn’t able to test this.

Battery Life

Another major focus of the under-hood improvements in iOS 9 is battery life. Apple says that an extra hour of typical battery life can be expected in daily use.

So how did the marketing fare in the real world? I don’t have an adequate rig set up to test battery life in some kind of semi-scientific fashion, but in day-to-day use, it has fluctuated greatly from beta to beta, as can be expected. But that made me a little worried when faced with the promise of significant battery life gains. The third and fourth betas exhibited almost impossibly good battery life; if anything, I would have guessed that the promised additional hour was an understatement. The fifth beta, on the other hand, appeared to completely ruin my iPhone’s battery life. It went from reliably lasting all day long to being nearly completely depleted by lunchtime. Around this time, though, I began noticing some other strange battery-related behaviour: accelerated depletion between the 20% and 10% warnings, for instance, only to plug it in and find that it was at 19%. I suspect one of the cells in my phone’s battery has died.

Therefore, it would be imprudent for me to judge the battery life of the gold master I’ve been using for the past week. Some days, it’s phenomenal; others, it’s poor, and — given the far better battery life of a few of the earlier betas — I think my phone is partly to blame.

One significant factor appears to be music playback, which I’m consistently seeing at the top of the list of power-hungry apps in Settings. Even after switching off Apple Music and choosing only local items for playback, I noticed occasional network activity from within the app. But Apple Music was included with the third beta, and its battery life was just fine. I have no logical explanation for this.

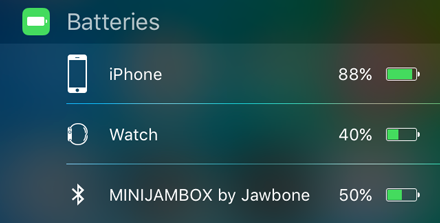

If you can’t get to an outlet, you’ll be delighted to hear that the low-power mode from the Apple Watch has made its way onto the iPhone. This mode disables all kinds of background processes, places the battery percentage in the status bar, and apparently disables some visual effects. After enabling low-power mode, though, I didn’t notice the omission of blurring, translucency, or any of the usual suspects on my iPhone – the only things disabled, as far as I can figure out, are Dynamic wallpapers and parallax effects. Apple says that an additional three hours of battery life can be expected after enabling low power mode, in addition to the extra promised hour. That’s not as significant of a gain as low-power mode on the Apple Watch, but you’ll still have network connectivity and all your apps on your iPhone. It’s a tradeoff.

In my testing, the low-power mode delivered, though not as I expected. The description is a little misleading: if you turn on low-power mode when you’re first prompted — at the 20% warning — you won’t eke out three additional hours; you’ll probably add an extra hour of life, at best. But if you go all day long in low-power mode, you’ll probably get the full three hours.

The battery life on my iPad has been exceptional, but isn’t it always? I’ve been using it regularly for the past few months, especially, and I haven’t noticed a decrease in battery life (but nor have I noticed any improvement, either). In case you were wondering, low-battery mode isn’t available on the iPad.

UI

After a major interface design overhaul that practically rewrote the HIG just two versions ago, it comes as no surprise that the UI of iOS 9 has, well, very few surprises. The corners of some things are a little more rounded and there’s a lot more space within action sheet items. But there are changes, indeed, and they’re systemwide.

San Francisco

Helvetica has been the signature typeface of iOS since its launch, which, for myriad reasons, makes for no small feat to consider replacing it. From a developer perspective, apps have only ever tested against it as a system font, so every label and every text cell fits just right. From a user perspective, it’s one of the things that makes iOS look and feel the way iOS does. For all it has been criticised for being generic, there’s an intricacy and geometric precision to its forms.

While I personally enjoy Helvetica, its shortcomings in user interfaces are obvious, even to me. Because its letter forms are similar, they tend to blur together and become ambiguous at the smaller sizes of most UI labels, buttons, and controls.

In my eyes, the days of Helvetica on iOS and OS X were quickly coming to a close with the introduction of the Apple Watch, bringing with it the typeface family known as San Francisco (or, for the retro users among you, San Francisco Neue).

Unlike OS X’s switch from Lucida Grande to Helvetica Neue last year though, the switch to San Francisco has gone largely unpublicized by Apple. They didn’t mention it during the WWDC keynote, and neither of their OS X or iOS promotional pages make note of it. For comparison, here’s what Apple wrote on the page devoted to Yosemite’s design:

For some, the choice of a font may not be a big deal. But to us, it’s an integral part of the interface. In OS X Yosemite, fonts have been refined systemwide to be more legible and consistent across the Mac experience. You’ll notice a fresh, new typeface in app windows, menu bars, and throughout the system. The type looks great on any Mac, and even more stunning on a Mac with a Retina display.

There isn’t an equivalent section for either iOS 9 or El Capitan’s use of San Francisco. I kind of understand this; the change to Helvetica in OS X had an outsized amount of attention placed to the change of system font, given that most users might not notice it. But San Francisco is an in-house typeface that’s completely unique to Apple’s operating systems, and it plays to the “only Apple devices work together so seamlessly” trope in their marketing, in a very distinctive way. Like Segoe — Microsoft’s in-house UI font — but unlike Roboto — Google’s — San Francisco is only available on its proprietors’ platforms. That is, while it was once possible to make a website look iOS-ey on other platforms by embedding Helvetica (Neue) as a web font — and while it is possible to make a website that looks like it comes from Google by doing the same with Roboto — it is not legally possible to make your website or app look like iOS 9 or OS X 10.11 on any platform other than Apple’s. San Francisco is not available as a web font, and it’s also not available in in-app font pickers. It is only to be used as a UI font, or where Apple deems appropriate. They control its use.

So what about the typeface family itself? San Francisco has been written about and dissected since its launch by myself, among many others, so I’ll try not to rehash too much. In a nut: I think San Francisco is extremely well-proportioned, looks fantastic, and performs very well as a UI font.

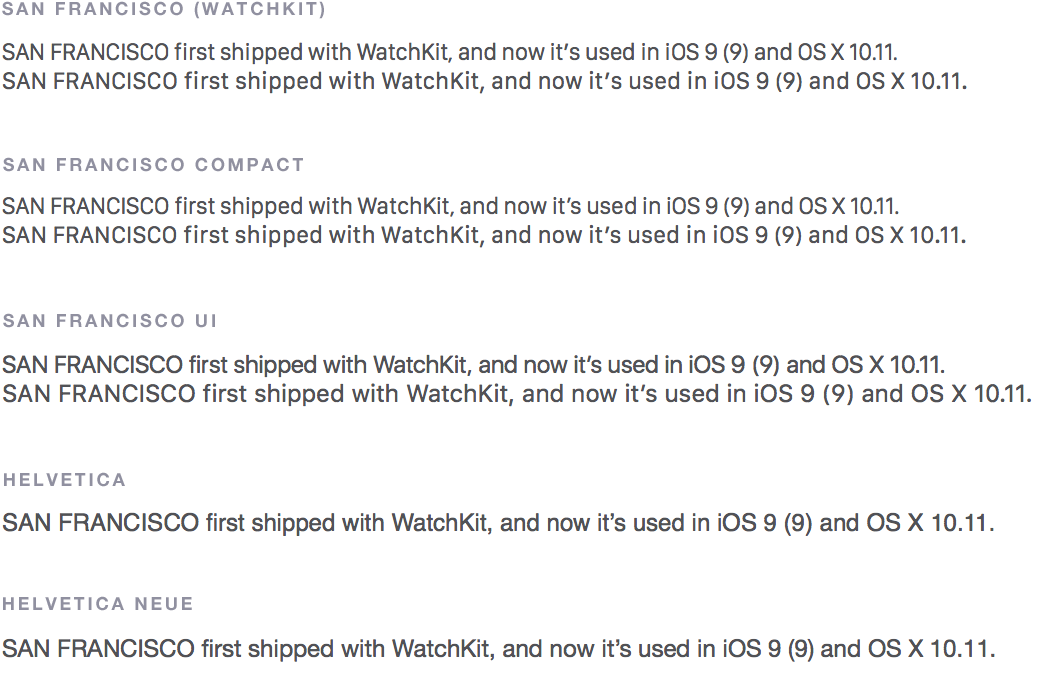

That’s a good thing, because it is now the one, true UI typeface across all of Apple’s operating systems, which means that the designers at the company thinks it works well and is legible on displays ranging from the poky-ass Apple Watch to a gigantic iMac, and everything in between. To make this more manageable, Apple has created two major versions of San Francisco: SF UI and SF Compact — née San Francisco, as shipped with WatchKit — that each contain Display and Text families, for a total of 42 font files. The Compact version is used exclusively on the Apple Watch, while the UI version is used on iOS and OS X.

But that’s not the whole story, because there are individual versions of the UI version specifically hinted and tuned for various purposes in both operating systems in which it is used. There are four different grades of the “regular” weight, presumably for better Dynamic Type support. These grades are not exposed to the end user and they’re not available to designers.

It all adds up to a fabulous family of typefaces that works well at pretty much all of the sizes at which it’s used. The lighter weight looks gorgeous displaying the date at the top of Notification Centre, while the regular weight is crisp and clear below the icons on the home screen. San Francisco shares the precise, metallic feeling of the DIN family — it replaces DIN in the Camera app — but is a little rounder, which makes it feel friendlier.

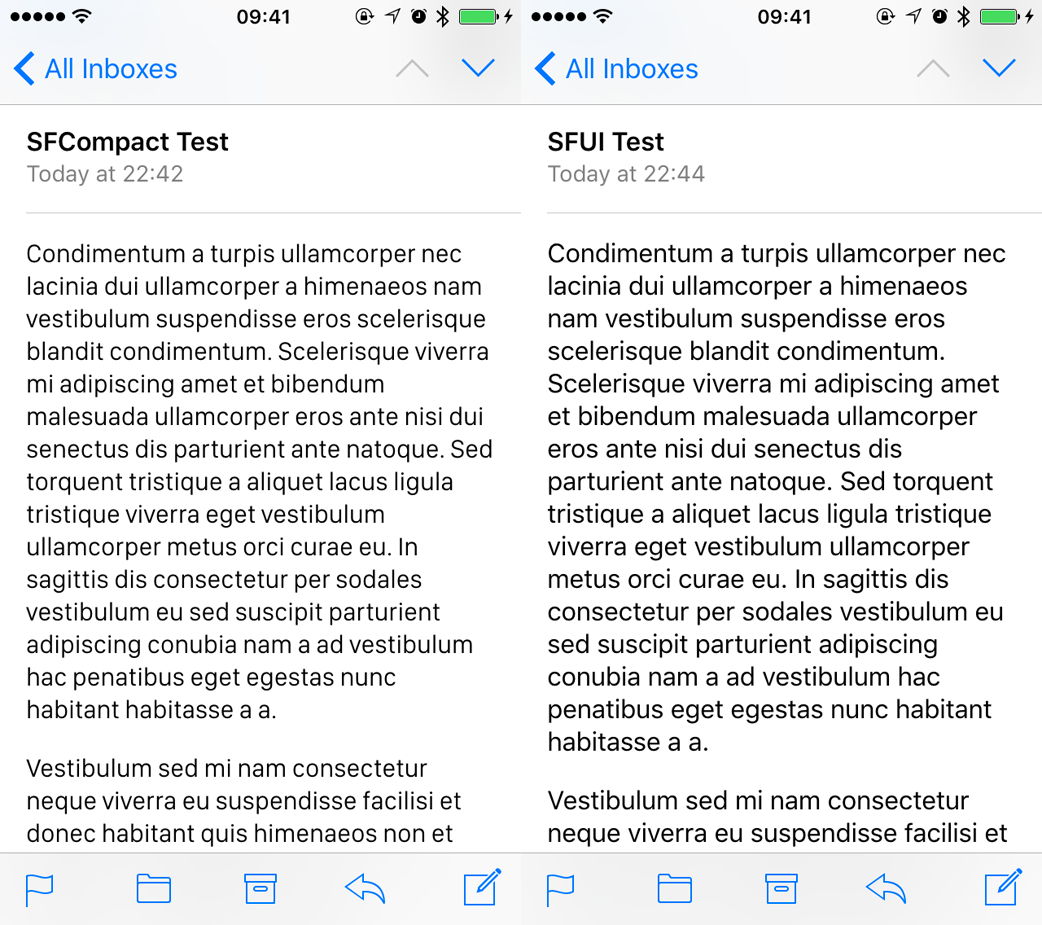

One of the main complaints I noticed about prior attempts to port San Francisco to iOS or OS X was that it too narrow, making it difficult to read. We now know this was the Compact version, with a much more appropriate UI version waiting in the wings. By opening up the characters compared to what we’re used to with the Compact set used in watchOS, it’s more legible at the sizes and with the amount of information it’s expected to display in iOS. Plain text emails, for example, are displayed in San Francisco; using the Compact version is noticeably less readable when it’s used in paragraphical text:

As transitions go, it’s subtler on the surface than, say, the one from Lucida Grande to Helvetica on OS X, but it’s extremely effective. It’s a much better UI font than Helvetica, and — dare I say — simply nicer in every application. Helvetica is a classic; San Francisco is clearer and more delightful. It’s possibly my favourite change in iOS 9, largely because it’s one that’s carried through the entire system with ease. It adds an additional layer of sophistication that Helvetica just can’t muster; it doesn’t have that quality.

Back Button

Somewhat more noticeable is the introduction of a back button in iOS. This has been part-and-parcel of every other mobile OS for a long time, so what’s different about Apple’s implementation?

Here’s how the back button is implemented in Android, according to Google’s developer documentation:

In almost all situations, the system maintains a back stack of activities while the user navigates your application. This allows the system to properly navigate backward when the user presses the Back button. However, there are a few cases in which your app should manually specify the Back behavior in order to provide the best user experience.

Most of the time, the system controls back button behaviour on Android, but developers can intervene:

For example, when a notification takes the user to an activity deep in your app hierarchy, you should add activities into your task’s back stack so that pressing Back navigates up the app hierarchy instead of exiting the app.

For example, tapping on a new text message notification and then tapping the back button will — by design — not return you to the last thing you were doing, but send you to the message list.

On Windows Phone, the back button behaviour is ostensibly much more consistent:

The first thing the Back button button does, as you might expect, is take you back one screen from where you are. Your phone remembers all the apps and websites you’ve visited since the last time your screen was locked, and will take you back one page each time you press Back, until you get to the Start screen.

[…]

There’s one exception to the rule: if you’re in Internet Explorer and press Back, you’ll return to the previous webpage you visited, rather than to the previous app. But once you’re out of it, Back goes back to taking you, well, back again.

Not exactly consistent in either case. Tapping the back button in an app might take you to the previous screen within the same app, might take you to a different app, or it might take you “back” in a way you may not expect. There are some who get used to this; there are others who want them to die.

And now, nine major releases in, iOS has one.

Happily, it’s implemented in a much more consistent way than any other major platform (and, I admit, it’s a stretch to call Windows Phone a “major platform”). It’s really very simple: if an app sends you into another app, you’ll see a back button on the lefthand side of the status bar. It replaces the assorted networking indicators, happens automatically, and requires no intervention from developers.

In the first month using iOS 9, I rarely used the back button simply because the multitasking shortcut is so engrained into my muscle memory. But, since I began to remind myself that it existed and is much more convenient than the app switcher, I’ve increasingly become reliant upon it.

However, its placement in the upper-left corner seems to fly in the face of Apple’s newer giant and gianter phones, relatively speaking. When Phil Schiller introduced the iPhones 6 last year, he addressed concerns that the much larger phones would be harder to use and hold (lightly edited for clarity — Schiller wasn’t exactly on-point during this presentation):

One of the things the team has worked on is to not only help [these phones] feel great in your hands […] but to make [them] easier to use one-handed. With iOS 7 last year, we introduced a new gesture: a side swipe gesture, thinking ahead to these phones and knowing that you’d want to use [that gesture] here.

The back button in most iPhone apps — or, at least, the good ones — is in the top-left of the navigation bar, but the inter-app back button in iOS 9 is in the status bar above it. It’s true that this will likely be used less frequently than the back button within an app. It’s also true that the app switcher can always be accessed with the home button, and with a 3D Touch from the edge on a 6S. But most devices running iOS 9 — at least, for a while – won’t have 3D Touch, but many of them will be larger. That makes the back button a little less than accessible, especially one-handed.

On my 5S, though, I think it would feel strange without it now.

Hierarchy and Order

With hundreds of millions of active users, any change Apple makes to the user interface components of iOS is necessarily going to cause a big ripple. Obviously, the biggest so far was the rollout of iOS 7, bringing with it equal amounts of praise and condemnation. Though I was generally positive towards it, there’s one thing iOS 7 did, design-wise, better than almost anything else.

Sheets Stacked on Light

Jog your memory with a look at the mess that was the hierarchy of iOS 6. If you think of different components that make up the iOS user interface — the wallpaper, icons, toolbars, and so forth — the Springboard lay somewhere in the middle of the UI stack. Dark linen — Apple’s background texture du jour — was probably the worst offender, appearing in elements that logically resided underneath the wallpaper — like folders and the multitasking tray — and in Notification Centre, which appeared overtop everything else.

In the video that accompanied the introduction of iOS 7, Jony Ive explained very clearly how the individual components of the operating system became organized:

Distinct, functional layers help establish hierarchy and order, and the use of translucency gives you a sense of your context. These planes — combined with new approaches to animation and motion — create a sense of depth and vitality.

The wallpaper became the base; nothing could be underneath it. Everything — icons, apps, folders, and the multitasking switch — would now be placed overtop the wallpaper. Finally, auxiliary, temporary “sheets” — Control Centre and Notification Centre — would appear over everything else. iOS 7 brought a clear order to the stacking of user interface components.

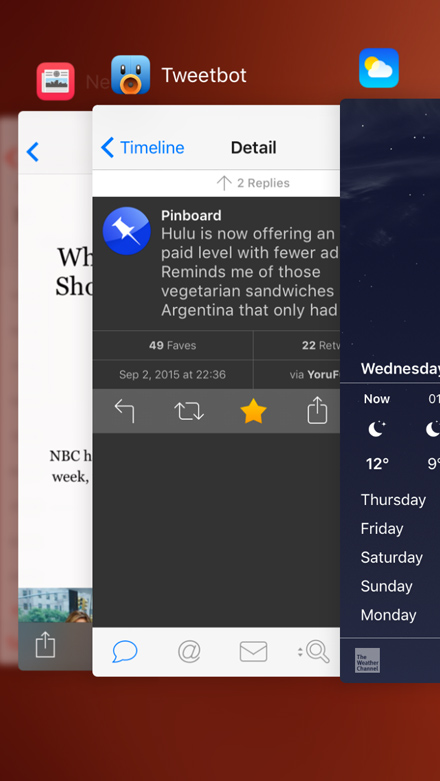

Multitasking

In that vein, the multitasking UI was revamped to shrink applications to tiles, floating overtop the background image, while the home screen icons appeared to float in their own tile, complete with a frosted background. This brought a sense of physicality to the OS, reinforcing the layering of the interface components.

But one thing has remained consistent since the introduction of multitasking in iOS 4: the most recent applications have always appeared on the lefthand side, while older apps are stacked to the right. It has been this way for five years: left to right, new to old.

The impetus for this change remained unclear to me, however. I wracked my brain for the past few months trying to understand why this is a better multitasking UI than the one it replaces, and I could only think of a single reason: its implementation of apps suggested by Proactive and Handoff. Previously, this feature felt like it was shoehorned in by placing the suggested app to the left of the home screen. This doesn’t make sense contextually, insomuch as that app is from a completely different device. Now, the suggestion is visible as a banner at the bottom of the screen, similar to the mini-player introduced in the Music app in iOS 8.4. It’s a more conceptually robust approach, as if the app resides outside of the boundaries of the device and can be pulled into view.

Now that I see 3D Touch working on the iPhones 6S, though, it’s clear why Apple chose to change the multitasking UI: it is now consistent with the back-paging swipe gesture. It hid under my nose this entire time.

A Metaphysical Interface

Apple’s choice to render many of the user interface layers with a background of blurred smears of translucent white. I think there was a significant conceptual rationale behind this decision — much greater than the aesthetics.

Your device’s display is a small-ish, very bright light with translucent colours suspended in differing amounts on top. User interface elements are literally blocking part of this light on their way to your eye. You can approximate the real-life effect iOS 7 is simulating by holding two sheets of paper in front of a lamp at varying distances from each other. In a sense, iOS went from being skeuomorphic — in the sense of attempting to replicate real-world analog materials — to skeuomorphic in the sense that it’s an almost literal interpretation of how an LCD works.

When placed in that context, the lack of shadows makes sense. Why would something entirely backlit draw shadows in any direction other than forward, straight into your face? Sure, there are exceptions: iOS 7 also, somewhat hypocritically, introduced the NSTextEffectLetterpressStyle attribute to Text Kit, which no developer I can think of has actually used because nobody is doing letterpress-style text on otherwise “flat” user interfaces. By and large, though, iOS 7 eschews typical shadowing because there are no shadows in this environment.

Except when the system is viewed in ambient lighting, that is. And that’s pretty much all the time, indoors or out. While the backlight remains the primary source of light, the foreground lighting with cast shadows onscreen. And if an element were to be overtop another in the virtual space, it should cast a shadow, right? Insist otherwise as hard as you want, but skeuomorphism isn’t dead on iOS; it has evolved and become more sophisticated.

In iOS 9, popovers, action sheets, and multitasked apps now draw a drop shadow behind them. It’s large and diffuse, and the kind of thing you only really notice in terms of shading rather than shadowing. The impression is that these popovers are significantly — nearly impossibly — closer to the user’s eye than anything behind them, kind of like the exaggerated virtual depth of folders and animations. It’s nice to have some sense of depth-by-lighting back.

Springboard

Another year begets another shuffle of applications installed by default. This year, Find My Friends and Find My iPhone receive the privilege of being preinstalled with iOS 9 and cannot be removed. I question the decision for the former to be built in, as much of its functionality is built into the Messages “detail” view anyway. I don’t know a lot of people who use Find My Friends; I suspect that many people will toss it into the same folder where Stocks, Tips, and Game Centre presently collect dust.

Happily, these are the sole additions to the preinstalled apps. While there is a new app by way of News, it basically replaces Newsstand, which is converted into a basic folder in iOS 9. Any apps or publications that resided within it are freed and displayed as regular apps. Passbook has also been renamed Wallet to more accurately reflect what it’s supposed to be, and Apple Watch is now, simply, Watch.1

And the Kitchen Sink

As of iOS 9, there are at least 33 applications installed by default, plus News if you live in a supported region and Activity if you have a paired Apple Watch. And, if you switch it on in Settings, there’s also an iCloud Drive app, but it’s hidden by default.

This certainly isn’t the first complaint you’ve read of this nature — and I’m sure it won’t be the last — but that’s a lot of default applications. It makes sense for Apple to try to cater to as much of the vast and heterogeneous iOS user base, but there is a necessary tradeoff. There’s more clutter and, therefore, less disk space afforded to a user’s own data. The latter is particularly noticeable when the company continues to insist that 16 GB is a reasonable entry-level capacity. Most baffling of all, however, is that the way Apple has configured default apps means that their updates are tied to system updates. The delta updates Apple introduced in iOS 5 and their much faster-paced update schedule lately have made this less of a burden, but it’s silly that a security flaw in, say, Find My Friends will necessitate a system update.

There are plenty of apps that we regularly ignore on our iPhones, and they seem pretty constant for most people. Who, for example, uses Compass regularly enough to keep it on their first home screen? It’s hard to make the argument that these apps represent the core functionality of iOS devices. Yet, Apple has already created a solution to this. With the introduction of the iPhones 6 last year, Apple began bundling the iWork suite of apps on the higher capacity models, but you could remove them. And, if it tickled your fancy, you could download them again later. There are probably ten apps that come preinstalled with iOS 9 that could easily fit into the category of nonessential apps that should be deletable. Fine, prevent me from deleting Messages or Safari, but why do I need to keep Stocks on here?

Wallpaper

iOS 9 shuffles the wallpaper selection, losing many of the legacy wallpapers that have shipped since iOS 7. Most of the gradients, coloured patterns, and so forth have been removed, along with many of the photos. Even the blue/green wave photo that was used in the earlier iOS 9 betas doesn’t ship with the release version.

Instead, we’re treated to some gorgeous macro photos of bird feathers that really highlight the precision of the Retina display. Only two non-Retina products run iOS 9, and Apple currently does not sell a single new non-Retina iOS device, so it makes sense to take advantage of the quality of these displays.

There are also some gorgeous new photos shot on a black background, which look especially nice on devices that have a black bezel around the display. It gives them the same kind of edge-less look as the Apple Watch display.

Unfortunately, there are no new Dynamic wallpapers included with the OS, only those that shipped with iOS 7, and there’s still no developer API for creating them. There are some motion wallpapers that will ship with the iPhones 6S, but those are more like videos as opposed to the existing programmatic Dynamic wallpapers, and require interaction before they will come alive. The seven colours of bokeh have, as far as I’m concerned, become stale. I’d love to see some new Dynamic wallpapers in both design and colour, but it doesn’t feel like it’s a priority.

iPad

If iOS 7 was the “look and feel” release and iOS 8 the “Christmas for developers” edition, iOS 9 is the iPad update. See, for all of the big changes in iOS 7 and 8, the iPad seemed like an afterthought; or, at the very least, the enhancements to the iPad during this era felt like they were only developed in parallel to any iPhone improvements. If you’re wont to radically oversimplifying the iPad’s software and UI, this isn’t much of a surprise. Since its introduction, the most frequent criticism of the iPad has been that it’s “just a big iPhone”. This is, in some ways, good — its software is recognizable, approachable, and easy-to-use. Apple played this criticism as a strength in early ads, promoting that “you already know how to use it”.

But it does have its drawbacks when it comes time to multitask, for instance: with only one app capable of being onscreen at a time, it makes researching and writing at the same time more cumbersome than it is on a computer running a desktop operating system. From the iPad’s perspective, this represents multiple tasks; from the human perspective, these two aspects define a single task. There are a enough little instances of issues like this that make the iPad feel less capable than it ought to be. Even if you’re like Federico Viticci and have managed to work within these limits — even making the most of the situation and treating them as an advantage — any improvement to the iPad’s multitasking capabilities certainly bolsters its post-PC credentials.

And bolster its credentials Apple has. It’s now possible to have two apps onscreen simultaneously, more easily toggle between two or more apps, and watch videos at the same time as other apps are open. Of course, having multiple apps visible at the same time isn’t necessarily the tricky bit; the hard part is making all of this additional capability feel easy to use when all there is to work with is a flat sheet of glass.

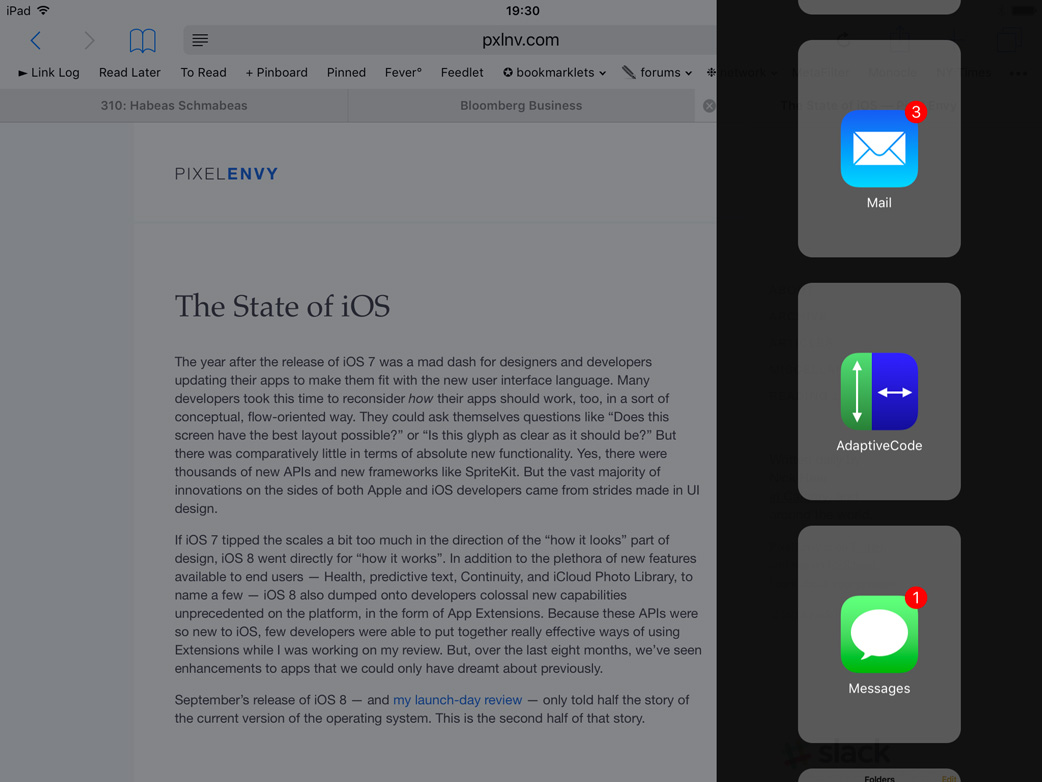

Slide Over and Split View

Since iOS 5, swiping from the top of the screen has brought down Notification Centre; since iOS 7, swiping from the left has gone back, and pulling up from the bottom has revealed Control Centre. Now, with iOS 9, Apple has completed their monopolization of edge-of-display gestures. Swiping from the right side of an A7-generation-or-later iPad will slide a different app overtop the currently-active one. It’s like proper multitasking; or, at the very least, bi-tasking.

Out of the box, most of Apple’s apps work in Slide Over, and most apps are expected to adapt Slide Over. The only exceptions that they envision are apps that require the entire screen, like a game, or a dedicated camera app. Everything else should adapt or die — my words, not theirs.

To switch between apps, there’s a “handle” at the top of the Slide Over area, similar to the one at the bottom of the lock screen that invokes Control Centre, or the control within a notification that expands it. Dragging down on this handle reduces the current app to a thumbnail and displays icons for available apps in a vertical strip of tiles.

Even with just the default apps, this feels like it will not scale well. Only four app icons are visible at a time in portrait orientation, and just three are shown in landscape. When most of the 60 third-party apps I have installed on my iPad support Slide Over, I imagine it will be unfeasible and inefficient. This is almost entirely due to each app icon being wrapped in a large tile-like shape that is slightly less opaque than its surroundings. I’ve been attempting to understand the justification for this since the WWDC keynote, and I still don’t get it. Perhaps it’s intended as a subtle indication that the app will not open full-screen or its intent will become more clear with the iPad Pro in hand, but it comes across to me as unnecessary chrome that significantly increases the amount of scanning and searching one needs to do to find a specific app.

Both this gesture and the gesture used to invoke Slide Over feel somewhat non-obvious to me, much in the same way that Control Centre and Notification Centre felt hidden when they were first introduced. As Slide Over uses the same symbolism as both Centres, it doesn’t take too long to figure it out, provided you know about it in some way prior to using it. The monopolizing of the righthand edge of the display also means that the forward-paging gesture in Safari no longer works, but perhaps that’s one way to figure out that this new multitasking option exists. Unlike either Centre, pressing the home button while the Slide Over view is active will not close the view; it will return the user to the home screen.

I wouldn’t dedicate this much discussion to the UI if I didn’t consider it one of the most important qualities of multitasking on the iPad. I wouldn’t be surprised if one of the biggest reasons the iPad didn’t have this feature until now is because of the challenge of trying to fit everything expected or required for a multitasking environment into the existing iOS UI language. Notably, there are things missing: there’s no close button or a way to “quit” the secondary app, for example, and it doesn’t appear in the app switcher. You just have to trust that the OS will do the right thing; no manual app management is required.

An app in Slide Over is the same 320-point width of iPhones 4 and 5, and they look the same as their iPhone counterparts. But even if an app is universal, it won’t appear in the Slide Over tray unless it meets the Apple-stipulated requirements:

- The app needs to have a Storyboard-based launch screen, not an image.

- The app must support all four device orientations.

- Most importantly, it needs to be linked to the iOS 9 SDK.

I’m not a developer, but I wanted to find out how easy this was. I downloaded a couple of older sample projects from Apple’s developer centre and followed the steps above and, within a few minutes, had them running in the Slide Over view. It seems fairly easy to implement, but I’m sure it will vary from app-to-app. The advantage will go to developers who have followed Apple’s suggestions and hints over the past few years, and who already have universal apps.

So how is it in use? Quite simply, the addition of Slide Over to the iPad has significantly changed the ways in which — and how often — I use my iPad Mini. While doing research for this review, I was able to have developer documentation open in Safari and pull in Notes any time I wanted to jot something down. Similarly, many nights this summer have been spent on my balcony reading articles with Instapaper or Safari, and pulling in Messages to chat with friends. These are simple things that have always been possible before, but its the increase in elegance and intuitiveness that really sets Slide Over apart.

Unfortunately, neither Slide Over nor Split View support simultaneously displaying two instances of the same app. A typical multitasking case for me is to have two documents open in Byword, or two webpages visible side-by-side. This is a surprising shortcoming for an otherwise-fantastic improvement.

One complaint I’ve long had with the iPad, ever since I bought my first — the iPad 2 — is that it does not ship with enough RAM. I’m not some kind of spec fiend, but when a web browser struggles to keep two tabs in memory at once, there’s a problem, both with the average size of web pages today and with the amount of memory available to handle them. My experience with Slide Over tells me that this remains the case, though significantly less so than ever before. It’s clear that Apple’s engineers have done a lot to improve the performance and memory consumption of iOS — tabs remain in memory longer with more open, and backgrounded apps seem to be dumped from memory less frequently. But it’s not quite as smooth as it could be.

Put it this way: the original iPhone, the 3G, and the first generation iPod Touch used effectively the same processor and memory combination. Do you remember how switching apps felt on those devices? Every time you pressed the home button, it felt like you were quitting the foreground app, and every time you tapped on an icon, it felt like the app was launching. It wasn’t painfully slow by any stretch of the imagination — certainly not for its time — but there was a perceptible amount of hesitance. Now recall how doing the same on a recent iPhone, like a 5S or newer, feels like you’re merely hopping between two apps (if those apps are built well).

Using the multitasking features on my iPad Mini in combination with often-heavy webpages open in Safari doesn’t feel like it lies at either end of these extremes. That’s good, in the sense that it doesn’t feel like I’m toggling in a kind of modal way, but it’s not as great when it doesn’t entirely feel like popping another app in for a peek, and then getting back to what I was doing. It’s a slightly hesitant, nervous feeling that I get from the OS, as though it wants to tell me just how much work it’s doing. Obviously, my iPad Mini is not of the most recent generation, but its hardware does represent over 50% of the iPads that are currently running iOS 9’s multitasking features.

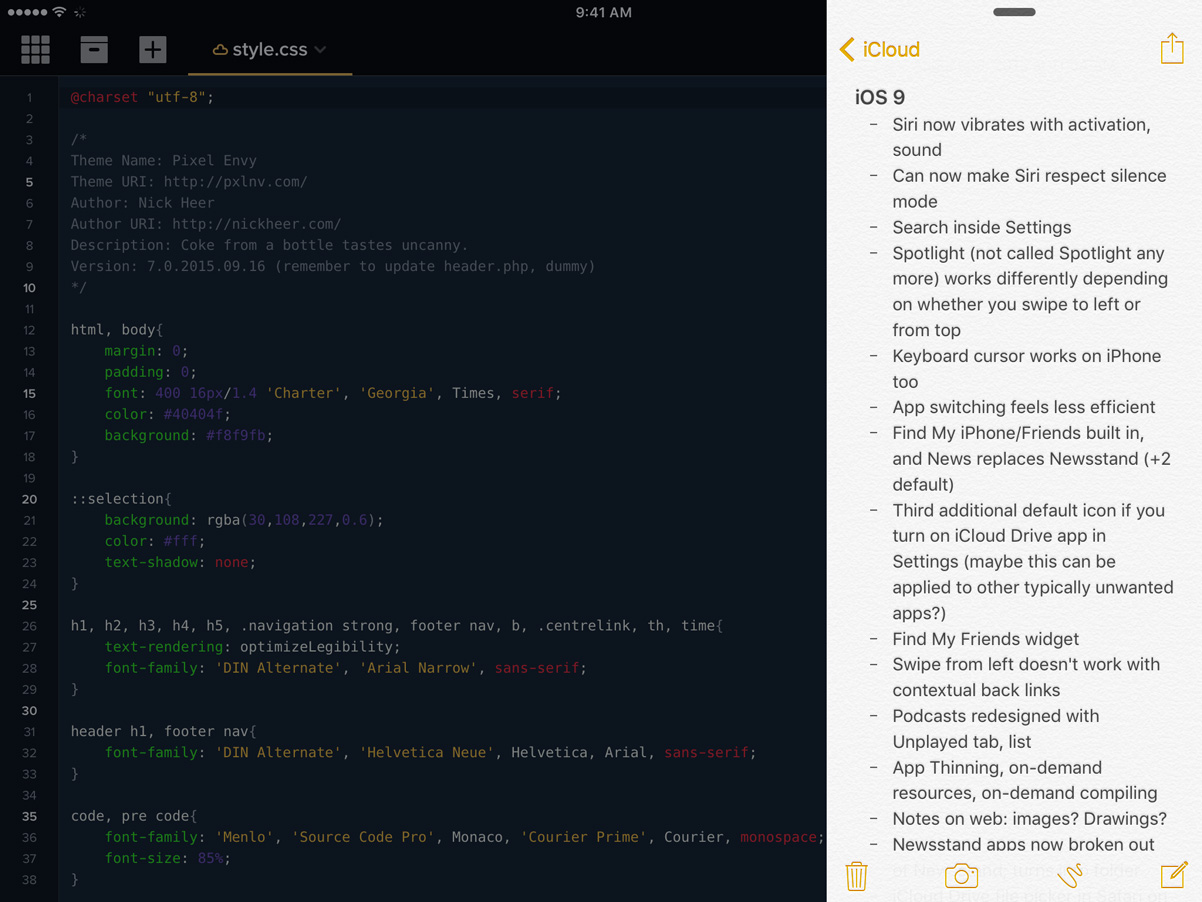

Split View

Split View is the next level of multitasking on the iPad, allowing you to run two apps side-by-side. Unfortunately, it requires kind of a lot of power (and RAM) to do this, so its availability is limited to only the newest iPads: Air 2, Mini 4, or Pro, naturally. I do not have an iPad Air 2, so I was unable to test Split View; Federico Viticci does, though, and did test it, so you should go check out his review for that and many, many other things.

I have played around with it in the iPad Simulator, though, so I feel somewhat qualified to chat a little about its UI and a few other related things.

The good news here is that if you’ve figured out the UI for Slide Over, you’re 95% of the way towards activating Split View. After pulling in a Slide Over view, you’ll see a small drag indicator on its lefthand side. Tap on this, the active app will shrink horizontally, and you’re now running two apps side by side.

In the simulated ways in which I’ve been able to test this — and what has been corroborated with others who have had hands-on experience — the two apps behave as if they didn’t know the other exists. You cannot, for instance, drag a link from Safari on the left into Messages on the right. The lack of drag-and-drop support — or any significant interaction, really — between the left and right apps is a surprising omission, especially since it’s an Apple product, and they’re kind of known for drag-and-drop. Though it’s not a standard interaction method in iOS, it would make a lot of sense in Split View.

Even without that, I can see this being a huge productivity boon. It’s only supported in the iPad Mini 4, iPad Air 2, and iPad Pro at the moment — of which only the first two are currently shipping — but it’s the kind of enhancement that defines the iPad as, in Tim Cook’s words, the “clearest expression of [Apple’s] vision of the future of personal computing”.

Picture-in-Picture

There’s another layer of multitasking available on top of the Slide Over and Split Views. iOS 9 allows you to pop video out of its app and float it overtop everything else on the screen. Also, when you press the home button while a fullscreen video is playing, the video will continue to play in an overlay. The video can be resized by pinching, and can be moved to any corner or even offscreen temporarily.

The video overlay is pretty clever too. If it’s positioned in the lower corners and you return to the home screen, the video will bump up to be just above the dock. The video will also typically avoid navigation bars.

Picture-in-picture functionality doesn’t work by default in all media views within apps; developers will need to make changes to allow users to take advantage of this. By default, videos played in Apple’s built-in apps — including Safari — will work with picture-in-picture. That means that any video you can stream on the web can be made to float above everything else, in any other app. That’s a lot more powerful than it sounds like — there are lots of universities that make recordings of lectures available for students, for example. Floating the lecture above Pages or OneNote is golden for students.

This is not a feature I have used extensively, and I don’t think it’s the kind of feature most people will use extensively. But the times that I have used it I’ve been thankful for its inclusion. I never observed it lagging or dropping frames, even when scrolling through complex web pages or my gigantic photo library behind it.

Command-Tab

There’s one more really cool multitasking feature that will be familiar to anyone who uses OS X: a task switcher. It looks pretty much the same as OS X’s, and it’s invoked with Command-Tab, just like OS X’s. It’s the kind of thing that’s optimized for the Smart Keyboard that will be available for the iPad Pro.

The iPad Release

All-told, the additional iPad-centric features in iOS 9 give a vital and impressive lift to a platform that has felt a little under-served for a while. The multitasking capabilities are impressive and genuinely useful — as I wrote earlier, it has increased the amount of time that I spend with my iPad, and the features that are coming to newer iPads make it much more likely that I upgrade sooner rather than later.

Keyboard

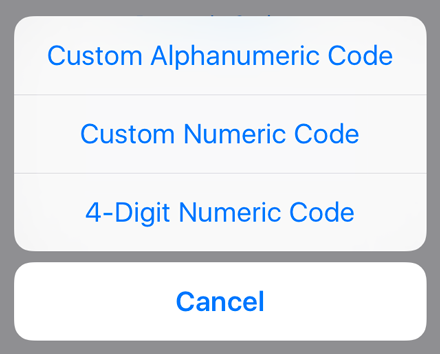

Precisely five hundred, fifty-five days ago, Apple decided to impart confusion on iOS users everywhere by redesigning the shift key on the keyboard. As I said last year, changes to the keyboard must be approached carefully — it is, of course, one of the most-used interface elements, and any change will be noticed. The decision to change the shift key in the way they did was not a good one.

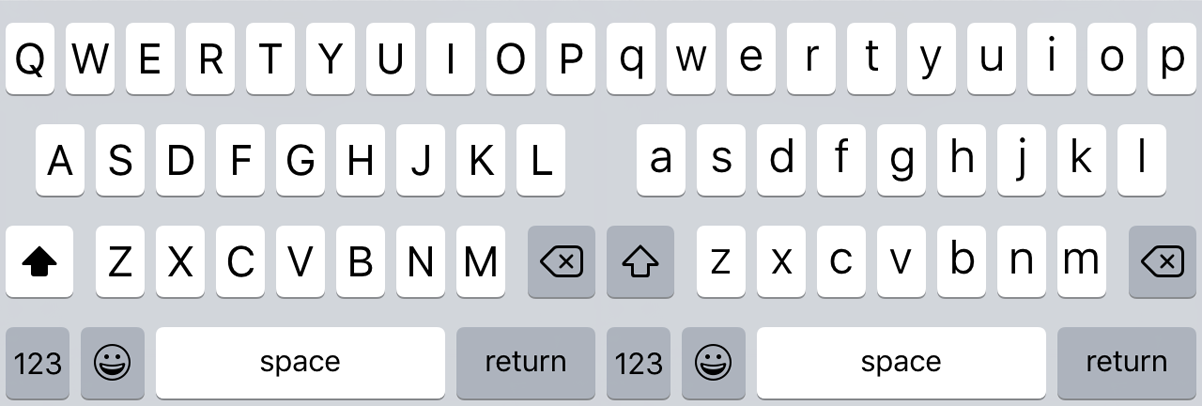

In iOS 9, Apple is not taking chances. Not only has the design of the shift key been refreshed to make the active and inactive states much more distinct, the keycaps now change from uppercase to lowercase when the shift key is not engaged. As this has always been something that’s possible in theory, it’s reasonable to question why it took eight years for it to make the cut. And it only takes a screenshot to figure it out.

d — and descenders — as with the letter j. That makes the letters difficult to align vertically, which you can see in the screenshot above. They’re all aligned to a baseline — that is, the bottoms of the letterforms all touch the same line — and the x-height — literally the height of the letter x — is vertically centred within the keycaps. But because ascenders and descenders go beyond the x-height and baseline, as they do, half of the letters of the alphabet look misaligned within their keycaps.

No matter how wonky this looks, I’ll bet this is huge for users with less-than-perfect eyesight, and others in the accessibility community. If you find it typographically disturbing, it can be disabled in Settings under Accessibility → Keyboard.

The keyboard has more tricks up its proverbial sleeve. On iPads, tapping on the keyboard with two fingers allows it to enter a sort of pseudo-trackpad state, where you can move the text insertion cursor around. It’s pretty great, especially in long documents.

Apple has also added formatting shortcuts to the top of the iPad and iPhone 6(S) Plus keyboards. I type pretty much everything in plain text, but for someone who uses productivity apps regularly, I’m sure it’s great. There’s no way Apple would ship it, but I’d love a Markdown version.

Searching Harder

Proactive

The machines are rising. We have told them so much about ourselves and, as we are creatures of habit, they have learned so much about us. And now they want to help us; that is, with a little bit of help from some Californian software engineers, too. Google has Now, which attempts to predict what you want to look at based on the time, your location, and what’s on your device. Apple would like to do something similar with an addition to Siri that they call Proactive.

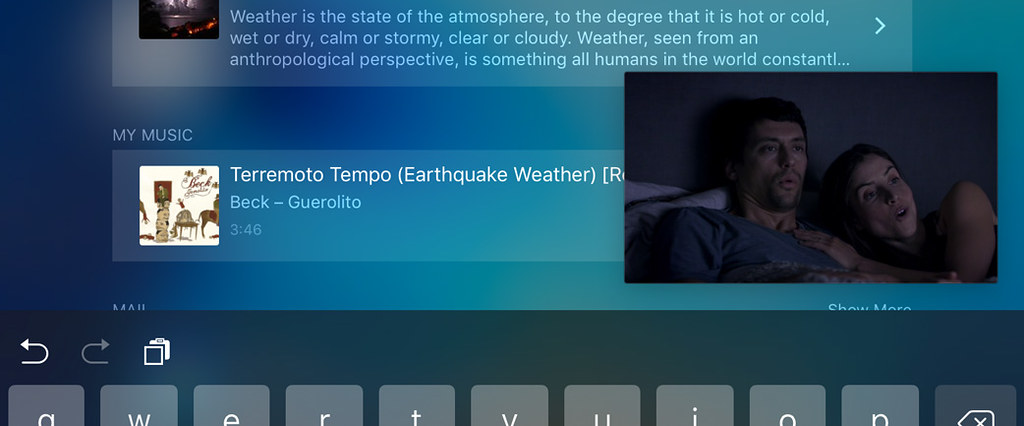

Proactive can be accessed with both Spotlight — which Apple now bills simply as “Search” in most places, but not in Settings — and Siri. In iOS 9, Spotlight can be accessed by swiping down on any home screen, or — making its jubilant comeback — swiping to the left of the first home screen. These modes are similar, but not identical: swiping downwards only shows Proactive app suggestions, while swiping to the left displays suggestions for contacts, apps, nearby businesses, and news.

All through this, Proactive is learning certain cues. When I wake up in the morning, it suggests Music, Instagram, and NYT Now. If there’s an event invitation in one of my emails, it suggests that I add it to my calendar at the top of the message. When I plug in my headphones, I see the last song or podcast I listened to on the lock screen. In fact, as I’ve been writing this review every evening over the past few weeks, I’ve seen Notes — where I’ve been keeping a bunch of my observations and ideas for this review — suggested by Proactive at around 9:00 or 10:00 each night. It’s a really nice touch.

The exception to this are the recommendations for nearby businesses which, naturally, requires pinging a server with your location. These are grouped into categories like Fast Food, Cinema, Nightlife, and gas stations, based on the current time of day. (I’m writing this review at night — can you tell?) Tapping on one of these circular icons launches a Maps search for that category. Unfortunately, it doesn’t automatically filter these results by those which are currently open, but it does sort by distance. This feature is only available in China and the US at launch, unfortunately; during the betas, it was functional in Canada and I really liked using it. I hope it comes back soon.

But, ever since the WWDC keynote, I’ve been perplexed as to why so much of this tentpole feature has been tucked away in Spotlight, given how much it can change the way customers use their phones. When I unlock my phone, I see my first home screen. On there are the apps I use most frequently; I would suspect most others’ phones are set up in a similar way. It’s unlikely that I’m going to make the effort to swipe one screen away, as I’ll find four or eight apps that are typically on my home screen already. Occasionally, as with the Notes suggestion above, I will see apps that are buried deep inside a folder, and that’s genuinely useful. I get the feeling that this is the first step in preparation for a more major push to modify the way we think of the home screen, but right now, it’s not radically changing the way I use my iPhone or my iPad.

I also don’t understand the logic by which apps and contacts are suggested. This is, of course, by design — it’s more magical when you don’t know what’s inside the hat, so to speak. Of the eight contacts suggested on my phone right now, seven are people I’ve recently texted, emailed, or called, which makes sense. Six of those people are on my favourites list in the phone app. The last of the eight suggested contacts is someone who is also on my favourites list, but who I have not called nor messaged in the past several months. Maybe that’s Proactive reminding me to get back in touch; I’m not sure. I’ve also seen a couple of instances of suggestions for contacts whose birthdays are coming up, but not always, and not with any particular rhyme or reason.

But often not suggested are non-favourite contacts who I am in regular contact with recently. Lately, there are a couple of people I’ve been speaking with by phone, text, and email, and not one of them has appeared in this suggested contacts area. I’ve since removed all but two of my favourite contacts in the hopes that I’ll receive a more relevant mix. Perhaps this works better for people in corporate settings, or others may potentially talk to a few dozen people every day.

Even if these suggestions become really great, I’m back to my lack of understanding of why this functionality isn’t front and centre, or part of the typical iOS workflow. When I want to message a friend, I open Messages, regardless of how much or how little I contact them; when I want to email someone, I fire up Mail. Providing suggestions is genuinely helpful, but when they’re presented in a way that doesn’t fit my learned usage patterns, I’m unlikely to use them regularly. The surprising exception to this, for me, was last year’s introduction of favourite and recent contacts to the app switcher. Apple has removed it this year, but I regularly used that feature. Perhaps I will learn to integrate Spotlight into my typical usage pattern after all, but it hasn’t come naturally yet.

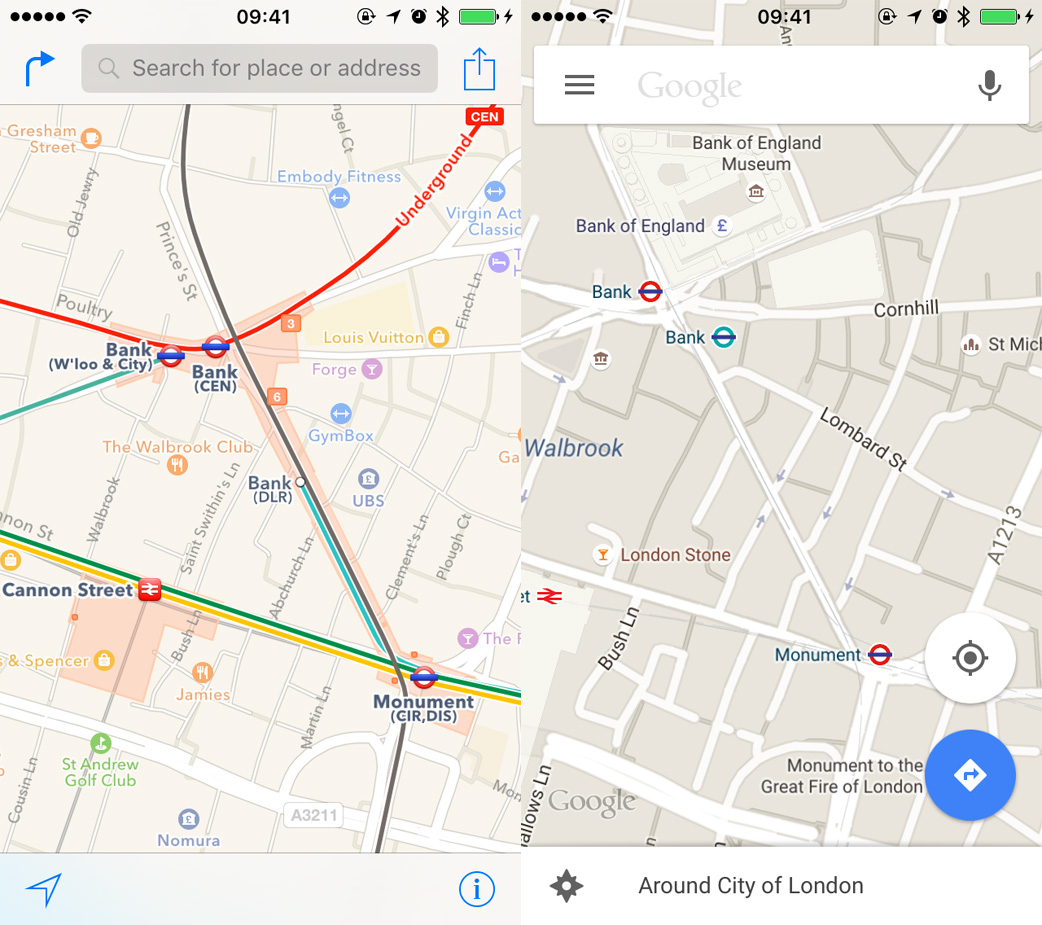

There are instances where Proactive goodness could conceivably appear in the places you would expect. For example, when you tap the search box in Maps, you’ll see the same higher-level versions of the business categories that Proactive suggests — instead of Fast Food or Nightlife, you’ll see Food or Fun. Tap on one of these broader categories and you’ll see all of the sub-categories: for Food, that would include Restaurants, Supermarkets (which displays as “Supermark…” on my phone, but never mind that), and, yes, Fast Food. Though these are not in any way predictive – it doesn’t use the current time to suggest nearby businesses — I find this integration far more natural, and it’s something I’ve regularly used over the past several months.

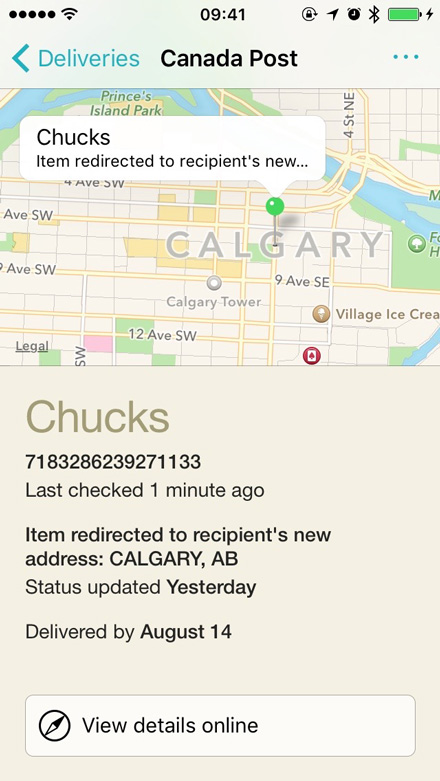

And then there are Proactive’s app suggestions. For a period of a few weeks, I had several parcels arriving, so I was regularly opening and checking Deliveries. But now, all of my parcels have arrived – less one; long story — and I don’t have much of a need for Deliveries at the moment. Though I haven’t opened the app for a while, Proactive continues to suggest it. It doesn’t seem to take much for Proactive to learn something, but it does seem to take a long time for it to forget stuff.

In practice, I’ve found it difficult to replicate this functionality with any reliability. A confirmation email from Hotels.com, for example, was detected perfectly, with the exception of detecting what time zone I booked the hotel in. But a plain text email like this produced unexpected results:

Hi Nick,

We’re having a party!

When: Friday, September 11 at 8:00 PM until midnight

Where: Jarvis Hall Fine Art

Hope to see you there.

(I should note that this email is fake, but Jarvis Hall really does run a great gallery in Calgary.)

In this case, Mail will detect the event in the email and display a banner across the top similar to that in iOS 8 for adding a new contact. However, it will not detect the location of the event, nor use anything in the email — not even the subject line — as an event title. Calendar also won’t create a placeholder event, and minor differences to the formatting of that message can fail to make the banner appear in Mail as well.

Perhaps most surprising is that receiving an ICS event file, the standard file format for event files in all calendaring applications, doesn’t display the banner in Mail nor does it create a placeholder event in Calendar. Colour me perplexed.

As far as I can tell, Proactive-enhanced calendaring is a temperamental animal. It does not behave consistently, which is frustrating, but when it does work, it’s magic. Like most seemingly-magical things — Siri, natural language search engines, automatic whatever — its limitations feel undefined and murky, and they’ll only be found by experimentation.

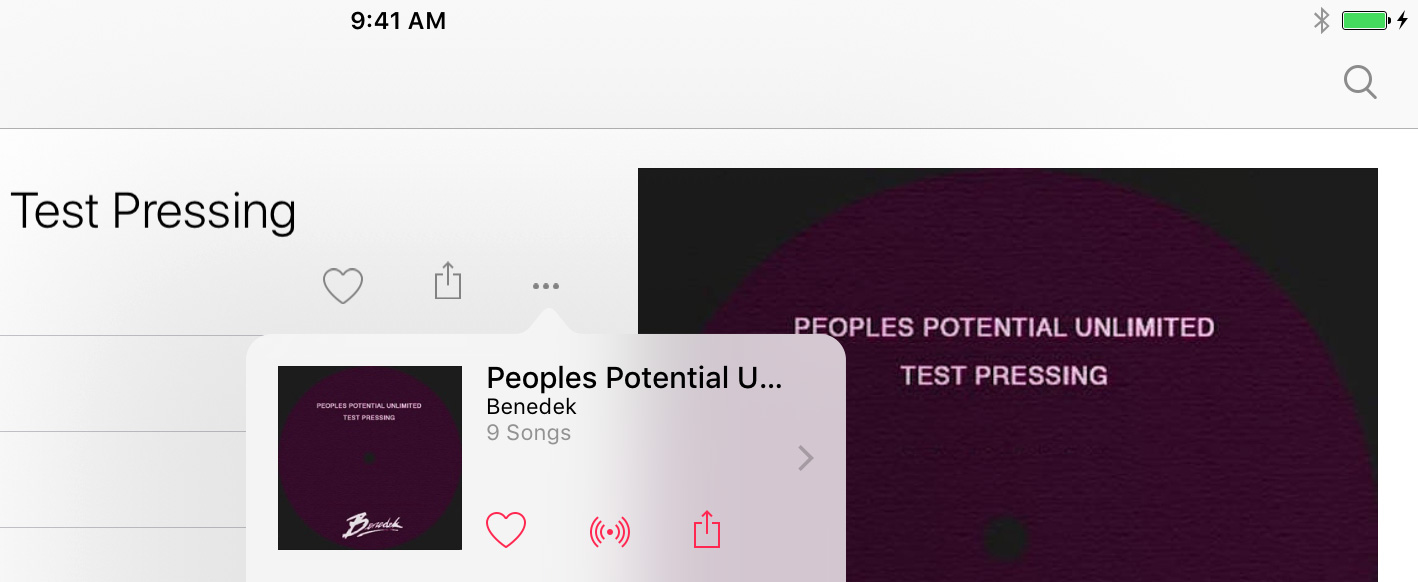

There’s one final touch bit of Proactive goodness, and that’s related to audio. When you plug in your headphones or connect to a Bluetooth system, the last-playing song will appear. This I like very, very much.

Spotlight

So what about enhancements to Spotlight that aren’t predictive? Well, iOS 9 has those, too, in a big way.

Remember the halcyon days of rumours that Apple would compete with Google by introducing a web search engine? Well, they’ve kind of done that, only it’s a much more comprehensive interpretation that searches content on both the web and on your phone, even within apps. And the only way you can access it is if you have one of Apple’s devices; there’s no webpage with a search box.

To make this functionality possible, Apple has been not-so-secretly crawling the web for the past several months. I first started noticing references to an Apple web crawler in January or February in my server logs, and references to AppleBot — as it came to be known — showed up at the end of March.

17.142.152.145 - - [31/Mar/2015:21:28:41 -0400] "GET /?p=15974 HTTP/1.0" 301 20 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_1) AppleWebKit/600.2.5 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/8.0.2 Safari/600.2.5 (Applebot/0.1; +http://www.apple.com/go/applebot)"

The AppleBot uses a familiar array of signals to index pages, including Schema, Facebook’s OpenGraph, and HTML structure, and has so far indexed a bizarre assortment of sites. I’ve spot-checked many of the sites that I typically visit, and I haven’t really noticed a pattern. Very high-traffic sites are in there, as you might expect, but sites with even moderate traffic seem to be chosen based on criteria I haven’t figured out. Pixel Envy is in there as a suggested website, but Stephen Hackett’s excellent 512 Pixels is not, and he’s way more popular than I am.

Perplexing indexing anomalies aside, the fact of the matter is that this represents a radical shift in Apple’s approach to search. Previous versions of iOS have been entirely dependent upon Microsoft’s Bing search for their web results. Now, Bing results are demoted, but still visible, in both Spotlight and Safari.

Also in Spotlight in iOS 9 are results from Twitter, web videos (like Vevo and YouTube), and pretty much all of Apple’s built in apps (including their content). And you can do conversions and other basic kinds of math, or check the weather.

Starting in iOS 9, developers can set up the content of their apps for indexing. For example, Television Time uses this API so that you can search for a show from Spotlight, and each result is linked to that specific part of the app (in this case, a television show). Spark continues its quest to be a total replacement email app by indexing all your mail, and Pinner indexes your Pinboard bookmarks. I’m glad to see Apple opening up this kind of extensibility in their OS; it’s so much better for it.

Siri

There are some enhancements and changes to Siri in this release, too. As one may reasonably have guessed, Siri in iOS 9 looks a lot like Siri on the Apple Watch, complete with an RGB histogram that represents audio waveforms. I’m not entirely sold on this logic, or lack thereof, but I quite like it — I think it’s the best Siri has ever looked.

Also inherited from the Apple Watch is a lack of the familiar “ding ding” chime when activating Siri. If you’re on an iPhone, you’ll only feel a couple of quick pulses of haptic feedback. It’s subtle, but it feels like a much richer, more personal experience. It’s hard to explain, but it’s the difference between a version of Siri that feels like cold software, and a version that’s more immersive and connected.

The rest of Siri’s audio feedback, like reading answers aloud, can now be set to be dependent on the position of the ring/silent switch. This combination of things can render Siri mostly silent, most of the time, which has given Apple the confidence to reduce the amount of time the home button must be held before Siri is activated. It feels more fluid and somehow closer, though I have noticed an increase in the amount of accidental activations I make. It’s genuinely not a big deal, though: Siri is faster than it has ever been, and there’s no chime to embarrass you in a meeting or class.

If you’re outputting sound from your iPhone via Bluetooth or the headphone jack, or you’re using an iPad or, presumably, an iPod Touch — both of which lack a vibrating motor — you’ll hear the activation chime, but no de-activation sound.

Changes to sound effects aside, one thing I’ve noticed in iOS 9 is a marked increase in Siri’s accuracy. I’m never sure whether this stuff is my imagination or not, but the reliability of Siri has gone up seemingly significantly over the past few months I’ve been using this new incarnation. I’m guessing that the Watch and the forthcoming Apple TV helped fine tune this, and the result is that I’m far more confident using Siri than I ever have been. Yes, it still — inexplicably — can’t edit reminders, but it’s better at understanding you when you do utter a command that it can obey. It’s a relatively small amount of progress, but the payoff is worth it.

But, like much of Siri’s functionality, it’s buried under a layer of guesswork and unexpected failures. You can’t, for example, ask Siri to remind you about anything in Photos or Music — say, if you found a playlist in For You that you wanted to listen to later. It also doesn’t work with some of the cues you might expect. For example, invoking Siri on a Safari page on your iPhone and asking it to remind you to check the page out on your iPad will create the reminder, but it won’t be triggered when you next switch devices.

More Intelligent, but Not Brilliant

Apple has clearly put a lot of work into all aspects of search. Proactive is one of their most ambitious efforts yet in the space, and it’s clear that Siri works better than ever, and can be tuned to your voice. The addition of third-party indexing to Spotlight is totally killer. All of these things come together to make iOS more personal and more user-friendly.

But no matter how much work has gone into all of these features, there remains the nagging feeling that Apple could have done more if they didn’t have such a hardline stance on user privacy. The flip side of the coin is, as Jack Wellborn quipped, “The reverse statement sounds even worse: ‘Google Now takes functionality seriously, but privacy is sacrificed.’”

I can’t be alone in wanting the best of both worlds: the privacy of Siri with the features of Google Now. But I’m not desperate, and it’s far easier for me to be patient with what iOS has now than to try to make Google Now as privacy-conscious as possible. It’s far from perfect, but at least I don’t feel like I’m turning tricks.

Safari

Safari View Controller

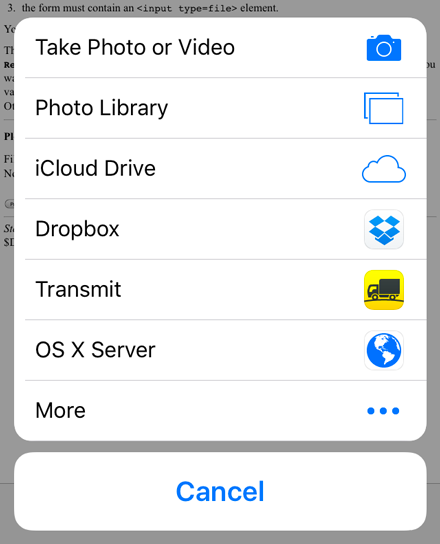

So far, iOS has come with two major APIs available to developers for including web content in their apps: UIWebView and — new in iOS 8 — WKWebView. The latter performs better, but they’re basically the same sandboxed, dumb web browser in an app, completely distinct from Safari.

iOS 9 includes an incredible new API for developers called Safari View Controller. Federico Viticci has a great explanation of this new API but, in a nut, it’s almost like running Safari directly within an app. There are shared cookies, which means your logins from Safari will transfer over, autofill is available, and it’s much safer for users as all browsing activity is isolated to the view controller.

I’ve been testing a few apps that have implemented SVC, and I can’t tell you how nice it feels. In most cases, it’s a subtle change, but the ways in which it improves over its predecessors improves the consistency of web browsing in different apps.

Content Blockers

“A widescreen iPod with touch controls” got big applause, while “a revolutionary mobile phone” got a massive reception. But “a breakthrough internet communications device” was merely greeted with tepid and polite clapping. With hindsight, we recognize the raucous applause opportunity we missed at Macworld 2007; the iPhone truly revolutionized the way we communicate on the web.

Before the iPhone, the mobile web was considered an anomaly. Very few sites considered how they would be rendered on the crappy WAP browsers included with most phones, from cheap flip phones to what was then considered a “smartphone”. Very few advertisers wasted their time or money trying to cater to these users.

But, as the mobile web grew after the introduction of the iPhone, everyone began to take notice. Companies large and small wanted their web properties to work well on phones, so developers began to create techniques to support them. Responsive web design was born of the desire to have identical content available for every visitor, no matter their screen size; after all, the mobile web is just the web. Browsers on both desktop and mobile adapted to these increasing demands. But as soon as performance improved, some developers would take advantage of it.

Also taking advantage of the increased JavaScript performance in web browsers were ad exchanges, analytics scripts, and other bullshit. Developers could use far more advanced techniques to try to measure everything from time spent on page to tracking every move of the user’s mouse throughout the page, to tracking a user within a site and around the web. Not only is this performance-intensive, it’s also invasive.

Because many websites converted to a responsive website and implemented a bunch of ad and tracking scripts, mobile users have been receiving the same bloated webpages as desktop users for years. A 10 MB text-only article — more common than you’d think — is inexcusable on the desktop, but at least it barely makes a dent in most broadband data caps. On mobile, though, the data caps are far more restrictive and the price per megabyte is way, way more.

Here’s the sticky problem: these crappy scripts and performance-intensive ads are how many websites make money these days. In order to pay for the — pardon me — content that readers consume, they have to put up with a bunch of stuff around it that readers don’t want. That much is understandable. But when a page’s weight is 10% content (and supporting code) and 90% advertising, that’s irresponsible and wrong. Something’s gotta give.

With iOS 9, Apple is bringing content blockers to Safari and Safari View Controllers. They’re only available on 64-bit devices for performance reasons, and they’re more complex than they seem on the surface. Yet, as far as users will be concerned, they provide for a far better browsing experience in a painless and unobtrusive way. Perhaps you’ve heard about this news.

So why are these extensions receiving significant media coverage? Well, let’s begin with the technical stuff. Most browser extension formats that you’re used to simply inject code upon loading a page, and they do so recursively — that is, the code also gets injected into each framed page within the parent page. This code may hide content on the page based on a stylesheet, or do something based on an additional script.

Content blockers are different. Instead of running during page load, the browser pre-compiles the JSON-formatted list of rules. This makes it way more efficient because the extension doesn’t have to load for each frame within a page, nor does it have to reload each time a new page is visited.

What kind of content can you block? Well, that really depends on what kind of blockers third-party developers create — unlike the misconception in plenty of media reports, Apple is not preloading an ad-blocker, nor are they implying that this is the intended use of content blockers. Indeed, plenty of third-party developers are utilizing this extension in different ways, from blocking adult content to silencing the internet peanut gallery.

But plenty of the content blockers available from third-party developers will be ad and tracker blockers. Unfortunately, like most iOS extensions, activating a content blocker is a bit buried. After downloading one or more of your choice from the App Store, open Settings, tap Safari, then tap Content Blockers and switch your newly-acquired blocker on.

I’ve been using Crystal for the past month or so and the difference it makes to loading times is, ahem, crystal clear. Page loads are reduced, often significantly, and I can have more pages open at the same time without triggering a refresh when switching tabs. It’s night and day.

Unfortunately, as has been pointed out, there are some ethical dilemmas that are inescapable. Blocking ads makes it harder for a website to earn money. But, while we’re not entitled to a website’s content, we are typically there for anything but the ads. If this were like television — where the balance between advertising and substance is typically tilted towards substance — the ethical argument would hold more weight. But it isn’t; the scales are tilted too far in the direction of stuff that isn’t substantial. Furthermore, there are plenty of very heavy scripts that load in the background that track you within a site, or even across the web. I didn’t ask for an omnipresent Facebook “like” button that tracks me everywhere, but it’s out there. Everywhere.

There’s one more issue I have with content blockers: the name. Ads are not content; comments are not content. It’s a bit of a misnomer, but I suppose “crap blocker” didn’t fly in Apple’s marketing department. Oh well.

If content blockers take off on iOS — and I think they will — there’s going to be a big shakeup. Things will necessarily change, and that’s why there’s been so much media coverage. But we will hopefully be left with a better web that’s less scummy, more respective of privacy, and nicer to mobile data caps.

Other Enhancements

There are a couple of other changes to Safari this year that, while not as headlining as content blockers, are important in their own right.

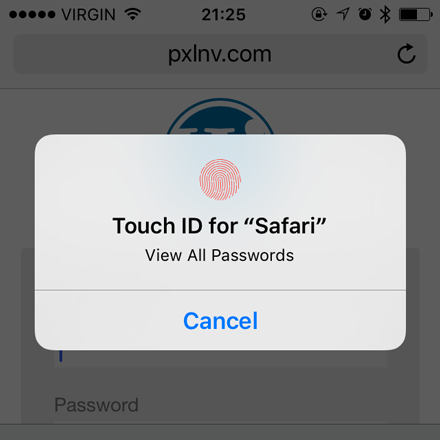

It’s also now possible to select from all available username and password combinations stored in iCloud Keychain when autofilling a form. There are lots of sites on which I have multiple username and password combinations, and the crapshoot autofill of iOS 7 and 8 bothered me on these sites. Sadly, it still isn’t possible to generate a password when registering for an account, like you can on OS X.

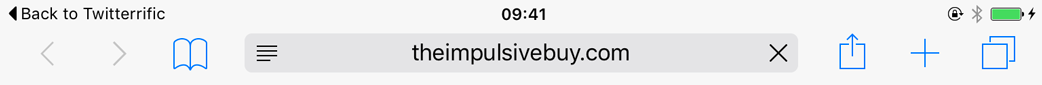

Finally, the Find In Page and Request Desktop Site options have been moved from the address bar to the sharing sheet. The latter is also available by holding the reload button, as is an option to reload the page without content blockers. This makes a lot more sense than burying any of these things at the bottom of the address suggestions.

News

With iOS 5, Apple added a new icon to the home screen: Newsstand, and it was a curious beast. It had the container-like behaviour of a folder blended with the dedicated multitasking icon of an app. But the intent was pretty clear: instead of having a bunch of news apps all cluttering up your home screen, why not have one place for publications of all sorts, indie and professional? These apps would look like the news, too, with icons that were masked and skewed to look like physical magazines and newspapers laying in wooden shelves.

While they were at it, Apple gave these apps some special permissions. Unlike any other app, Newsstand apps could change their icon with each issue, because magazines and newspapers change their front page with every issue. These apps could also change the app description at will, without having to submit a new app build to the review team. Perhaps the most significant difference between a Newsstand app and a generic app is that they were allowed to refresh in the background, something otherwise unallowed with the APIs available at the time.

Even with all of these additional capabilities and hundreds — perhaps thousands — of mainstream publications supporting it, Newsstand never really took off. Perhaps users didn’t like the idea of opening multiple apps — sorry, publications — every day to read what’s new in each, or maybe they didn’t want to pay for several individual subscriptions. The redesigned Newsstand icon in iOS 7 certainly didn’t help, as it no longer indicated to the user whether the publications inside had been updated. Meanwhile, the background refresh capabilities previously exclusive to Newsstand apps were opened up to every app.

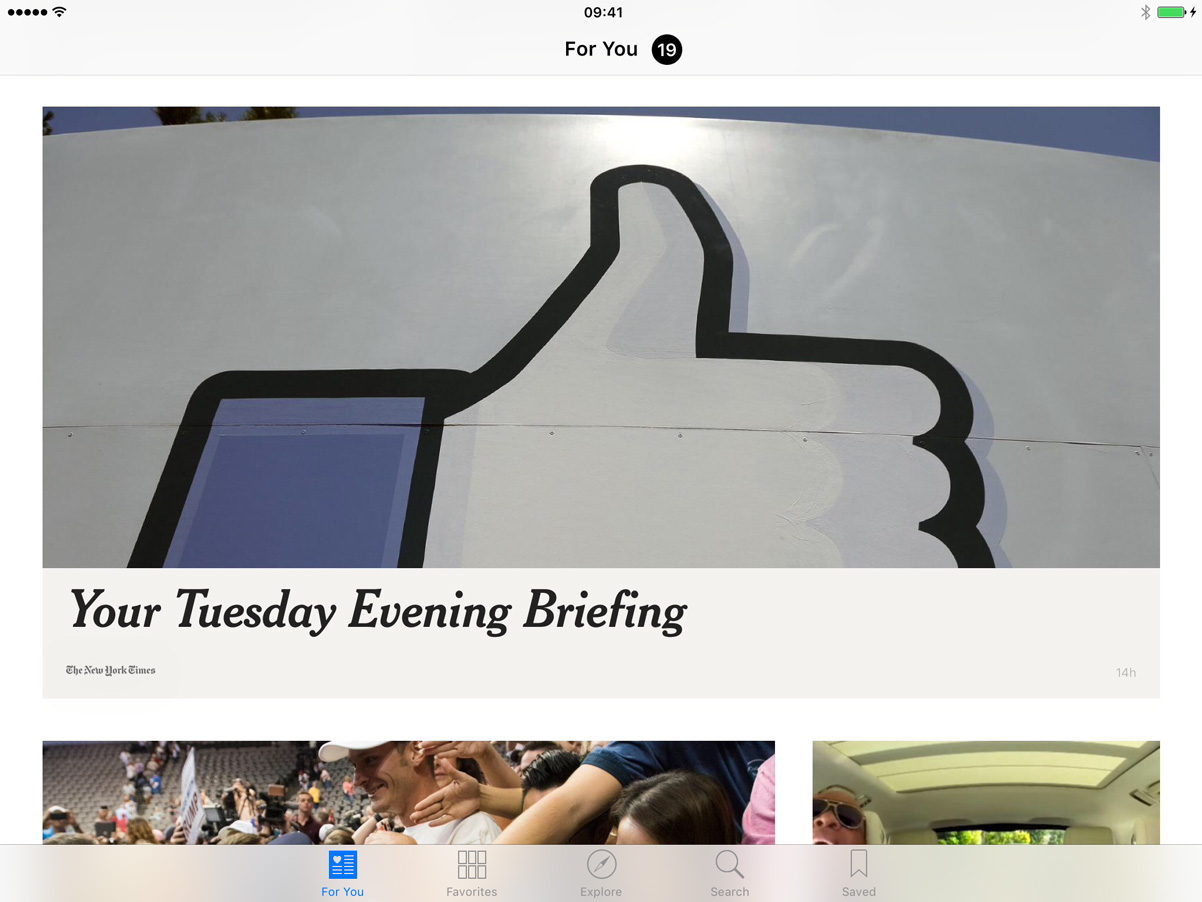

News is a different animal altogether. Instead of being a folder of separate apps, it’s just one app with all publications within it. Publishers also don’t have to create custom apps because News relies on RSS, which means all publications — large and small — can be included.

For publishers, there are two ways of getting your app included in News. The first way is to head to iCloud.com and sign in with your account. Then, launch the News Publisher app. You can fill in your details, submit your RSS feed, and upload a logo. You can even submit multiple RSS feeds for different categories or sections. For example, if I were so inclined, I could create separate feeds for linked items and full-length articles, and they would appear as different sections within News. Apple recommends using only full-content RSS feeds, as opposed to truncated summary-style feeds.

The obvious advantage of submitting your feed through News Publisher is that it will be included in the searchable News directory. Feeds are automatically crawled for keywords and topics; publishers do not have to fill in a lengthy metadata or description form which, let’s face it, would likely be abused anyway. Being in Apple’s directory, though, requires a review from Apple, and I know of perfectly legitimate publications that have been rejected with the same kind of vague rationale as some App Store rejections.

Fortunately, if a website has an RSS feed, there’s another way to add it to News. In Safari, just tap the Share icon and scroll across the bottom row of actions until you find Add To News. Tap this icon and the sharing sheet will disappear. There will be no visual confirmation of any kind, but the site will be added to News.

When you launch News for the first time, you’ll be asked to subscribe to several publications and topics that you’re interested in. Apple refers to both publications and topics as “channels”, and they have quite the variety of both. You can also subscribe to topics, for when there’s something in the news you’d like to keep an eye on from any publication. As this is Apple, you won’t find Playboy or Penthouse in News — not even just the articles. But it has built-in topic detection for all items, and it does not censor topics that Apple might otherwise consider “mature”.

The biggest difference between RSS and ANF is that the latter supports in-story ads and monetization, while the former does not. Publishers using ANF can opt to use their own advertising network and keep all of their revenue, or they can use iAd from which Apple receives a 30% cut of revenues. RSS feeds do not support this kind of advertising, but News will not block or otherwise undermine sponsorship posts.

Additionally, there’s no way for publishers to set up a paywall or require authentication to read their articles. This seems like a logical next step for the platform, perhaps even repurposing the name Newsstand to allow publishers to offer paid subscriptions.

News, then, starts to feel kind of like a glorified RSS reader with a custom format soon to be available, and a monetization layer on top. But News comes with the same kind of personalization features as Apple Music. Tapping the heart icon in the bottom toolbar while reading a story tells News that you’d like to read more articles like it in the For You tab.

As with Music, this works better in theory than in practice. Because it isn’t an automated process, generating a profile of your particular interests and things you enjoy requires you to manually intervene regularly, and I’m not sure a tiny heart icon in the lower toolbar is a convincing way of doing that.

Apple says that News also uses the stories you read to help establish trends for the For You section. my expectation would be that reading and liking stories within News would surface other articles related to those, but from publications I do not typically follow. However, I haven’t really noticed this in practice — every story in my For You stream right now is either from a publication that I already follow, or is from a publication writing about a topic I already follow.