Post-Post-P.C.

A question the technology press loves to ask is some variation of what supplants the smartphone? and the answers are always unsatisfactory. Mainly that is the case because it does not seem like the right question. The smartphone is a near-perfect convergence device that has touched every fibre in the fabric of the world. But I think it is a perennial question because it is a device that still feels new; a personal computer, on the other hand, seems like a permanent fixture. For many people, the computer on our desk or lap feels like it has always been there.

What if it made more sense to ask: what comes after the P.C.?

It is a question worth asking not because the P.C. is old, but because we can ask if there are things which could be done better. That might be something the P.C. does right now, but not as well as we imagine it could, or it is something we wish were possible but is limited by the form factor.

In Apple’s world, the answer to this question seemed to be the iPad. While Apple began referring to the post-P.C. era well before its introduction, the iPad was the device which supercharged ideas about moving beyond the P.C. and doing everything from this new era of mobile-first devices. Yet even though it was a sales hit, particularly in its first few generations, the capabilities of the iPad have been an ongoing struggle and controversy.

Partly that is because of software design choices. iPadOS is built on iOS; it is an evolution of an operating system made for touch screens — which is a good thing — and, more specifically, for touch screen phones. It means every advanced capability we take for granted in MacOS — multitasking, layers of application windows, pointers, multiple display support — has needed to be rethought and rebuilt for a tablet-specific environment. It means we are fourteen years into the iPad experiment and, even though its screen has grown by three diagonal inches since it debuted, it remains a device that still feels connected to the 320 × 480 pixel display it rode in on.

Eyeful

My dad bought his first digital camera in 2004, a Nikon Coolpix 4500. I remember that bizarre swivelling camera design about as well as I remember walking into the store to buy it with him; it also happened to be an authorized Apple reseller.

On one table was an iMac G4 paired with the surprisingly good Pro Speakers. But it was the model on another table I remember most: a Power Mac G5 connected to a 30-inch Cinema Display. I could sit down in front of the “world’s fastest” P.C. and open Safari or iTunes on the world’s biggest display. Even using those boring applications felt like the business when they were projected onto this huge canvas.

Anyone who has cooked with enthusiasm knows how cramping a foolscap-sized cutting board is. Displays are exactly like that. Working on a large, high-resolution screen — just like the one I sat in front of in that Apple reseller twenty years ago — feels almost limitless, constrained only by its two dimensional form.

So what happens if the display and, with it, the impression of the entire computer were abstracted away to create an environment?

Vision Curious

Apple is calling this “spatial computing” — not virtual or augmented reality, though those are components of it. And the device with which it is entering the field is called the “Vision Pro”. That name has been dissected to no end for its suffix, Pro. It implies this is not the version for consumers, but for a more selective group of individuals: specifically, those who have $3,500 in dicking around money. But it is the Vision part of the name that I am most interested in. It is not only describing the computer-in-your-eyes aspect of the product, it conveys to me this is Apple’s perspective on where it thinks personal computing will be heading. This is truly Apple’s vision of the future. Trepidations with this version aside, I think I get it, and I think I am on board.

Even if this product, which is supposed to usher it in, is almost on users’ faces, it still seems so far away. Virtual and augmented reality are, in my mind, part of a brand new industry — but it is not. In 2023, IDC says, 8.1 million headsets were sold worldwide. For comparison, in 2014, the year before the Apple Watch went on sale, less than five million smartwatches and fitness bands were shipped, according to the now-defunct Smartwatch Group. Then Apple molded that segment in its image. Of course, how many smartwatches and headsets are being sold does not tell you how many are actually being used; it is entirely plausible that eight million drawers have a headset stuffed near the back.

Even knowing all of this, I cannot help but feel Apple is redefining the personal computer in a way that has so far eluded other attempts from it and others. Perhaps the eventual Vision line will not entirely replace the Mac, but I could see that being the case for lots of people, not just those who would also find an iPad or an iPhone an acceptable working device. Most of us have jobs that could benefit from having more space, even if we are just spending time in spreadsheets or building an email campaign. Putting a development window and a browser window side-by-side on my 27-inch iMac is workable but cramped. I am imagining how great it could be if I could put those windows all around me, plus more for different browser widths. A desktop projected across an entire field of vision is, in theory, more capable and more elegant than multiple monitors, especially if there is no discernible loss of quality.

At least, that is how it appears from the outside looking in. I have not even glanced at a Vision Pro in person, let alone spent time with one. (That is why this post is titled “Vision Curious”, not “Vision Pro Impressions”.) But it is not hard to see an ambitious roadmap: to one day augment or even replace the Mac with something simultaneously more expansive and more portable. Apple is not the first to think along these lines, but it is the first to have a full stack of hardware, operating system, and applications created specifically for this endeavour. No other company has all of those things; they are all dependent on processors of others’ design, or third-party operating systems — or both.

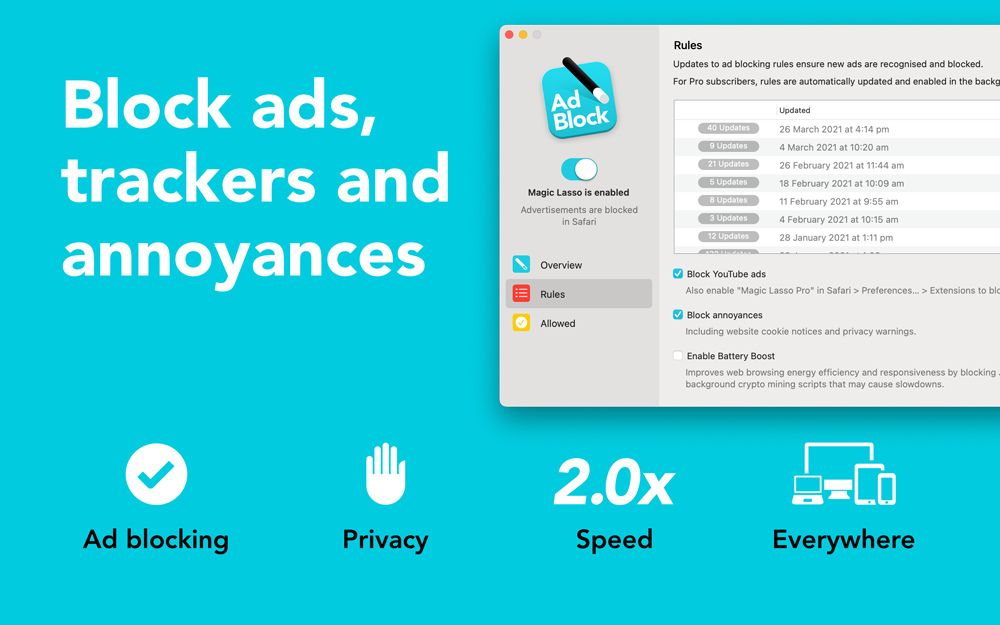

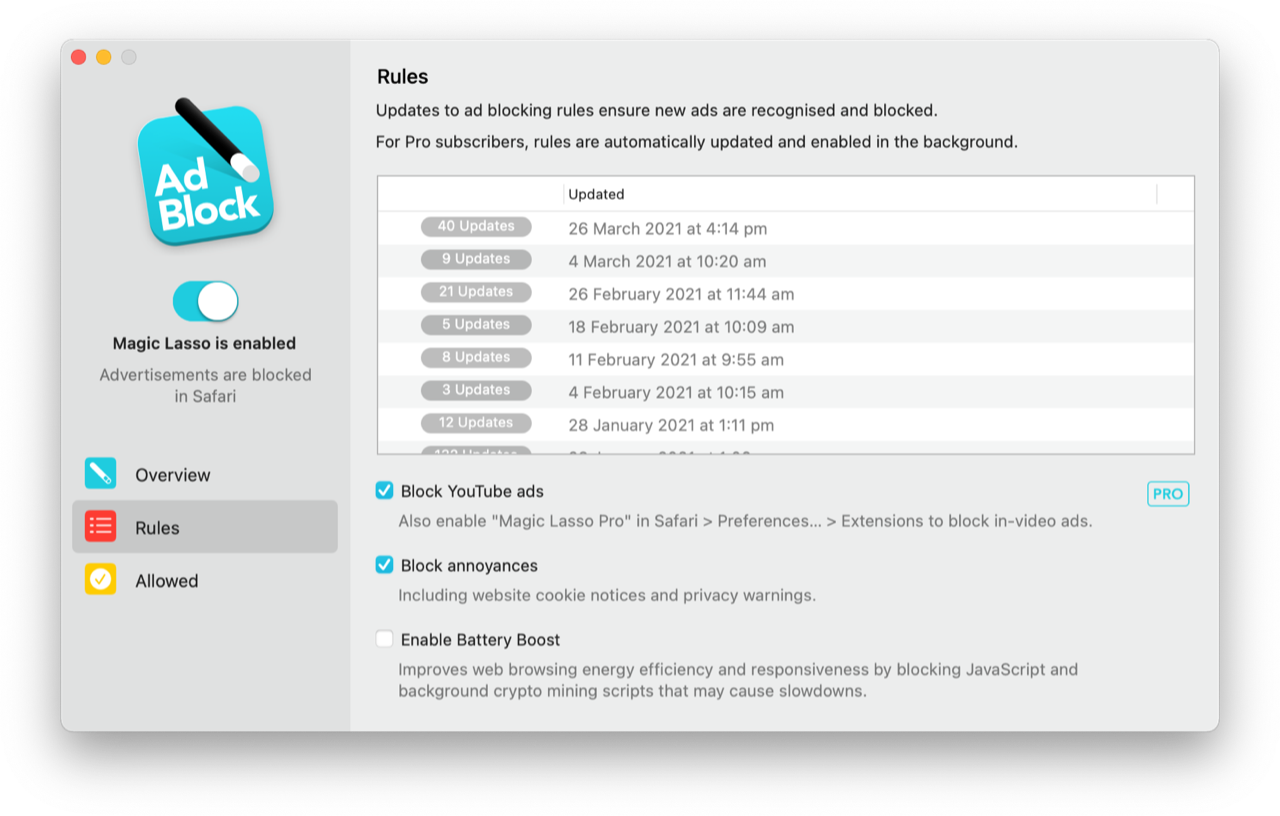

If I am right — if the intended trajectory of this thing is successful and it one day takes the role of the Mac for many people — the Vision Pro will benefit from a gentle introduction. Face it: computer goggles look real weird. It is probably a big reason for the failure of Google Glass, and why Microsoft’s HoloLens is only used in niche contexts. We have a lot to get used to if this category is to become commonplace, so it helps if users need to learn as few new things as possible. Perhaps the most captivating thing about what I have seen so far is the way Apple presents the software as exactly what you are used to. Even the native VisionOS versions are pitched as “the familiar apps you know and love”. As someone uneasy with this entire product category, this grounding element is important.

Of course, those same apps exist in an entirely new context. This is the part where my curiosity takes over and I have no expectations. I have read as much as I can from those who have used the Vision Pro in what are, as of writing, limited demonstration environments. I am only able to imagine what it feels like to be fully immersed in the article you are reading, a movie you are watching, a game you are playing, or something you are making.

The Vision Pro sure sounds compelling. It looks about as good as computerized ski goggles are capable of, it has some familiar qualities to prevent users from getting completely lost, and all the demo impressions I have read suggest it is a transformative experience.

Hold on, though; here is the catch: while Apple says the Vision Pro is capable of displaying a MacOS environment as a 4K display within the virtual environment, VisionOS is based on iPadOS. Given the system’s design and the way one navigates within it, this is not a surprise. Yet, here I am, already questioning whether VisionOS will be able to keep Safari tabs in memory or if it will reload them after using other applications, like iPadOS has always done. Can Photos in VisionOS create Smart Albums? Heck — can it even display Smart Albums?

Maybe VisionOS is great in ways iPadOS has not yet been able to achieve. I am optimistic. However, my impression from a distance is that a wearable computer with the capabilities of MacOS — though not necessarily running MacOS — is compelling to me, but a wearable computer with the capabilities of iPadOS is less so.

It is not just system abilities at stake, but platform restrictions, too. After Apple announced the unsurprising rules by which it would govern purchases made on iOS via links in third-party apps, I was reminded of how the Mac is an outlier in the company’s platform strategy. Every other operating system Apple makes is based on iOS in technology and policy. The Mac is special by choice. Apple could always extend more advanced operating system functionality to its other devices if it chooses. If Apple’s intention is for this headset to lay the groundwork for a mainstream Mac-adjacent platform, I hope it will not be constrained by console-like policies.

Aside from the platform-specific apprehension of an iPadOS-based product, I have questions about isolation. A headset is also necessarily personal, qualities of which Apple has both leaned into and distanced itself from. In its announcement, Apple mentions the “private […] 4K display” connected to your Mac, but is also careful to explain how “users stay connected with those around them” through the EyeSight display on the headset’s outward-facing plane.

However, none of this permits others to share the same experience. Sometimes, this is desirable, saving us from creative directors peeking at a work in progress and offering their incisive feedback unprompted. Sometimes, though, it creates friction. How many of us watch movies with a partner, or want to collaborate with a group of people on a project, or want to show the friend next to us this really funny video? Apple would probably say there are solutions for these things, like AirDrop, AirPlay, and SharePlay. These little interpersonal moments necessarily become digital.

I do not know that this is good or bad, just radically different. The Wall Street Journal’s Nicole Nguyen wrote about changing interaction standards for headphones, since many have passthrough audio. A fully immersed person is another step up from that. I still think it is only respectful to remove headphones when talking to someone, just like it is always right to always turn the lights off when you are the last person to exit a room.

Apple also makes products that are better tailored to those kinds of situations, and it would be happy to sell you those. Maybe that is the way of the future for a lot of people: more devices for more specific contexts. Smartphones are convergence devices but so are laptops — just ones that are differently capable and less portable. A headset does not replace a P.C. as a do-it-all device for nearly any occasion. However, if you spend most of your computer time alone — and many of us do — it could be an example of a deconvergence device. People love their phones, so why try to replace them? They are a hub around which every other piece of technology revolves, from the headphones and smartwatch you choose to the vast app-centred economic sector.

The things which are piquing my interest and the things I am concerned about are not exclusive to the Vision Pro; lots of tech companies have tried similar concepts. If Apple is putting its weight behind it, it is clearly trying to transform it from a somewhat niche interest to major platform. Definitely not today, maybe not tomorrow, but one day it will be commonplace — or, at least, that is the pitch.

The introduction of the Vision Pro felt entirely different than any recent product from a famously user-conscious company like Apple because this first version is clearly not intended for adoption by millions. Even if Apple sells every single one made this year, it will only be of minor relevance to the company’s total sales. It feels closer to a first draft than most recent all-new Apple products. For the iPad and Apple Watch, for example, none of the first-party apps were shipped in compatibility mode. Its relatively restrained launch reinforces how different the Vision Pro is in its first iteration.1

But a muted debut does not necessarily imply a lack of confidence in this category. On the contrary, I think the first impressions I have seen so far, while carefully choreographed for choice journalists, have been more convincing than an Apple executive’s enthusiastic presentation ever could be. Maybe it is a testament to marketing susceptibility, but this is the first time I have felt a headset like this has made sense. The early Oculus demos I experienced twelve years ago were technically impressive but I did not see how it could fit with what I am interested in. What I have seen from other efforts in the intervening years is a focus specifically on “augmented reality” and “virtual reality”. But gaming is not my bag, and neither is immersion in a “metaverse”, and neither, still, are persistent projections in my eye everywhere I go — as far as I know. But being able to read, write, browse the web, edit photos, and design things on a room-filling scale in high resolution with many of the tools I already use? That is exciting.

Apple’s term for this has been “spatial computing”, and I do not think that is a pure blue ocean invention of language to make it harder to compare Apple’s thing to other headset. It sounds right. There are certainly elements of augmented and virtual reality, but those are components of a more expansive imagination of what can be done when a powerful computer sits millimetres in front of your eyes.

It is poetic for the Vision Pro to ship barely more than a week after the Mac turns forty. I can hardly imagine a world without the Mac and, in a Wired interview with Steven Levy, it seems Greg Joswiak cannot either, saying it is “a product that defines who we are”. I do not think the Mac needs to die for spatial computing to succeed. However, it appears we are at the beginning of another forty-year trajectory, and I am cautiously on board.