Jason Snell again graciously allowed me to participate in the annual Six Colors Apple report card, so I graded the performance of a multi-trillion-dollar company from my low-rent apartment. There simply aren’t enough column inches in his report card for all of my silly thoughts. I have therefore generously given myself some space here to share them with you.

As much as 2020 was a worldwide catastrophe, it was impressive to see Apple handle pandemic issues remarkably well and still deliver excellence in the hardware, software, and services that we increasingly depended on. If there wasn’t widespread disease, Apple’s year could have played out nearly identically and I do not imagine it would have been received any differently.

Now, onto specific categories, graded from 1–5, 5 being best and 1 being Apple TV-iest. Spoiler alert!

Mac: 4

It will be a while before we know if 2020 was to personal computers what 2007 was to phones, but the M1 Macs feel similarly impactful on the industry at large. Apple demonstrated a scarcely-believable leap by delivering Macs powered by its own SoCs that got great battery life and outperformed just about any other Mac that has ever existed. And to make things even more wild, Apple shoehorned this combination into the least-expensive computers it makes. A holy crap revolutionary year, and it is only an appetizer for forthcoming iMac and MacBook Pro models.

Aside from the M1 models, Apple updated nearly all of its Mac product range except the Mac Pro. The iMac Pro only dropped its 8-core config, but pretty much everything else is the same as when it debuted three years ago.

The best news, aside from the M1 lineup, is that the loathed butterfly keyboard was finally banished from the Mac. Good riddance.

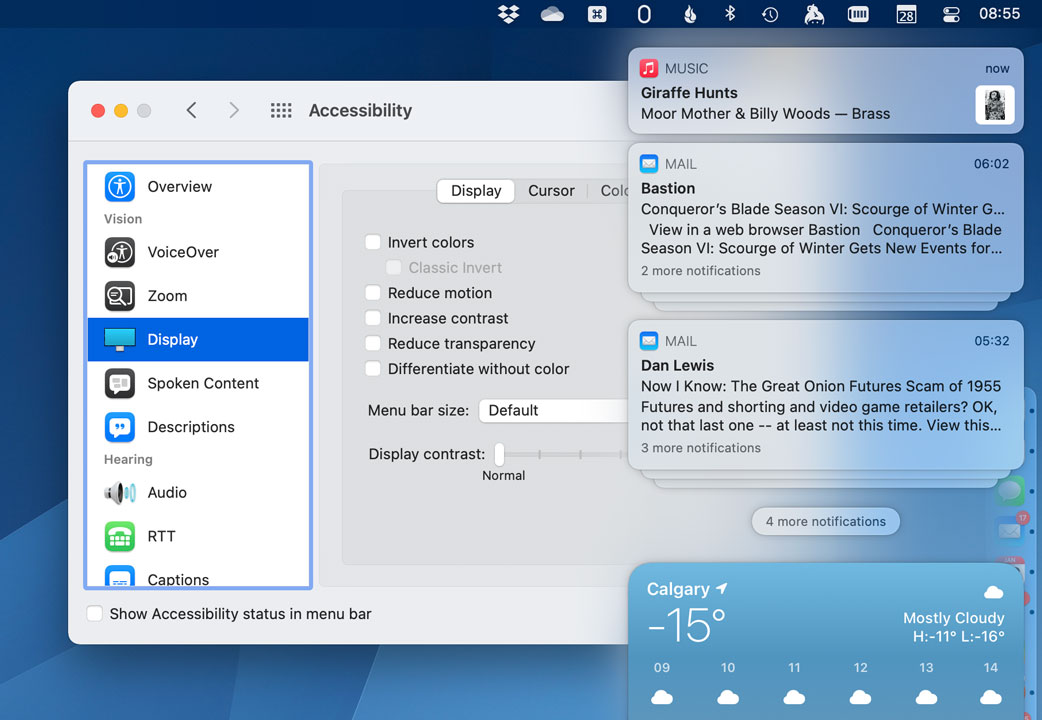

MacOS Big Sur is a decent update by recent MacOS standards. The new design language is going in a good direction, but there are contrast and legibility problems. It is, thankfully, night-and-day more stable than Catalina which I am thrilled that I skipped on my iMac and annoyed that I installed on a MacBook Air that will not get a Big Sur update. Fiddlesticks. But Big Sur has its share of new and old bugs that, while doing nothing so dramatic as forcing the system to reboot, indicate to me that the technical debt of years past is not being settled. More in the Software Quality section.

iPhone: 4

I picked a great year to buy a new iPhone; I picked a terrible year to buy a new iPhone. The five new phones released in 2020 made for the easiest product line to understand and the hardest to choose from. Do I get the 12 Mini, the size I have been begging Apple to make? Do I get the 12 Pro Max with its ridiculously good camera? How about one of the middle models? What about the great value of the SE? It was a difficult decision, but I got the Pro. And then, because I wish the Pro was lighter and smaller, I seriously considered swapping it for the Mini, but didn’t because ProRAW was released shortly after. Buying a telephone is just so hard.

iOS 14 is a tremendous update as well. Widgets are a welcome addition to everyone’s home screen and have spurred a joyous customization scene. ProRAW is a compelling feature for the iPhone 12 Pro models, and is implemented thoughtfully and simply. The App Drawer is excellent for a packrat like me.

2019 was a rough year for Apple operating system stability but, while iOS 13 was better for me than Catalina, iOS 14 has been noticeably less buggy and more stable. I hope this commitment to features and quality can be repeated every year.

Consider my 4-out-of-5 grade a very high 4, but not quite a 5. The iPhone XR remains in the lineup and feels increasingly out of place, and I truly wish the Pro came in a smaller and lighter package. I considered going for a perfect score but, well, it’s my report card.

iPad: 3

The thing the iPad lineup has needed most from the late 2010s was clarity; for the past few years, that is what it has gotten. 2020 brought good hardware updates that has made each iPad feel more accurately placed in the line — with the exception of the Mini, which remains a year behind its entry-level sibling.

But the biggest iPad updates this year were in accessories and in software. Trackpad and mouse compatibility updated a legacy input method for a modern platform, and its introduction was complemented by the new Magic Keyboard case. iPadOS 14 brought further improvements like sidebars, pull-down menus, and components that no longer cover the entire screen.

Despite all of these changes, I remain hungry for more. This is only the second year the iPad has had “iPadOS” and, while it is becoming more of its own thing, its roots in a smartphone operating system are still apparent in a way that sometimes impedes its full potential.

After many difficult years, it seems like Apple is taking the iPad seriously again. I would like to see more steady improvements so that every version of iPadOS feels increasingly like its own operating system even if it continues to look largely like iOS. This one is tougher to grade. I have waffled between 3 and 4, but I settled on the lower number. Think of it as a positive and enthusiastic 3-out-of-5.

Wearables (including Apple Watch): 3

Grades were submitted separately for the Apple Watch and Wearables. I have no experience with the Apple Watch this year, so I did not submit a grade.

Only one new AirPods model was introduced in 2020 but it was big. The AirPods Max certainly live up to their name in weight alone.

Aside from that, rattling in the AirPods Pro models was a common problem from when they were released and it took until October 2020, a full year after the product’s launch, for Apple to correct the problem. Customers can exchange their problematic pair for free, but the environmental waste of even a small percentage of flawed models is hard to bat away.

AirPods continue to be the iconic wireless headphone in the same way that white earbuds were to the iPod. I wish they were less expensive, though, particularly since the batteries have a lifespan of only a couple of years of regular use.

Apple TV: 1

I guess my lowest grade must go to the product that seems like Apple’s lowest priority. It is kind of embarrassing at this point.

The two Apple TV models on sale today were released three and five years ago, and have remained unchanged since. It isn’t solely a problem of device age or cost; it is that these products feel like they were introduced for a different era. This includes the remote, by the way. I know it is repetitive to complain about, but it still sucks and there appears to be no urgency for completing the new remote.

On the software side, tvOS 14 contains few updates. It now supports 4K videos in YouTube and through AirPlay, and HomeKit camera monitoring. Meanwhile, the Music app still does not work well, screensavers no longer match the time of day so there are sometimes very bright screensavers at night, and the overuse of slow animations makes the entire system feel sluggish. None of these things are new in tvOS 14; they are all very old problems that remain unfixed.

The solution to a good television experience remains elusive — and not just for Apple.

Services: 4

No matter whether you look at Apple’s balance sheet or its product strategy, it is clear that it is now fully and truly a services company. That focus has manifested in an increasingly compelling range of things you can give Apple five or ten dollars a month for; or, if you are fully entranced, you can get the whole package for a healthy discount in the new Apple One bundle subscription. Cool.

It has also brought increased reliability to the service offerings. Apple’s internet products used to be a joke, but they have shown near-perfect stability in recent years. Cloud-based services had a rocky year for stability in 2020 and iCloud was no exception around Christmastime but, generally, the reliability of these services instills confidence.

New for this year were the well-received Fitness+ workout service and a bevy of new TV+ shows. Apple also rolled out services to a bunch more countries. But this focus on services has not come without its foibles, as Apple aggressively promotes subscriptions throughout its products in advertisements, up-sells, and push notifications to the irritation of anyone who wishes not to subscribe. Some of these services also introduce liabilities in antitrust and corporate behaviour, something which I will explore later.

HomeKit

I have no experience with HomeKit so I did not grade it.

Hardware Reliability: 3

2020 was the year we bid farewell to the butterfly keyboard and, with it, the most glaring hardware reliability problem in Apple’s lineup. A quick perusal of Apple’s open repair programs and the “hardware” tag on Michael Tsai’s blog shows a few notable quality problems:

“Stained” appearance with the anti-reflective coating on Retina display-equipped notebooks

Display problems with iPhone 11 models manufactured into May 2020

AirPods Pro crackling problems that were only resolved a full year after the product’s debut

Overall, an average year for hardware quality, but an improvement in the sense that you can no longer buy an Apple laptop with a defective keyboard design.

I suppose this score could have gone one notch higher.

Software Quality: 4

The roller coaster ride continues. 2019? Not good! 2020? Pretty good!

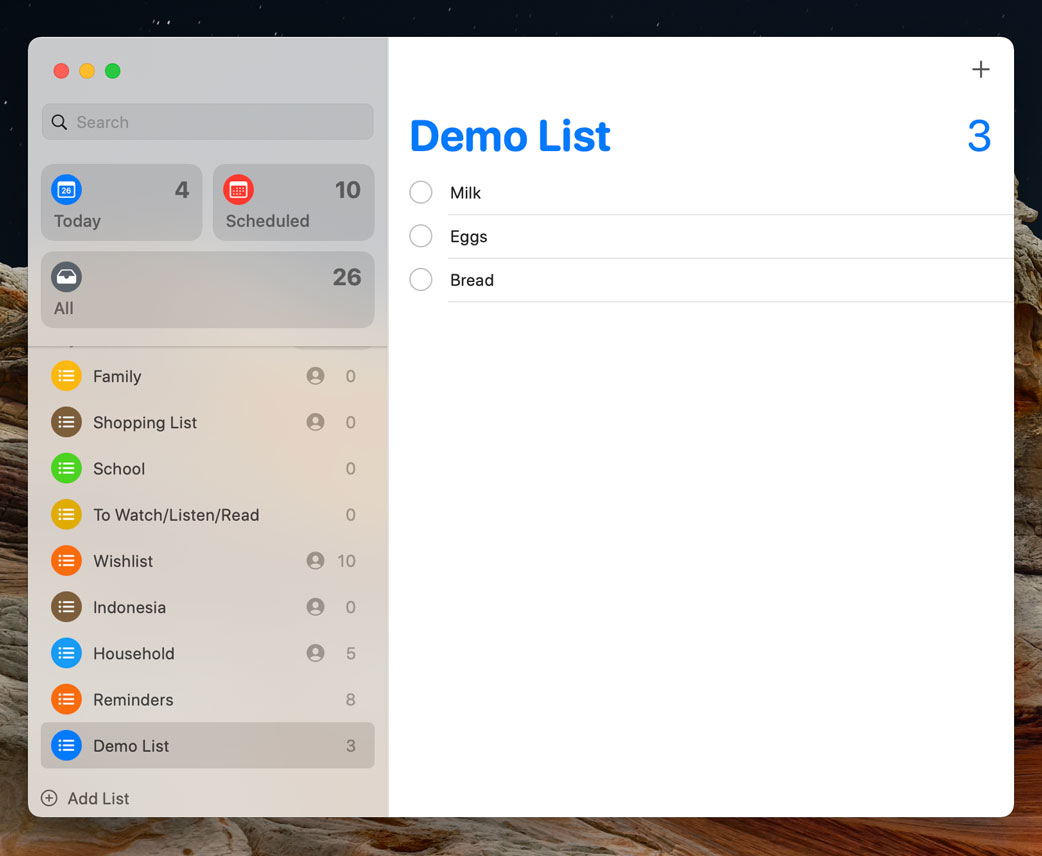

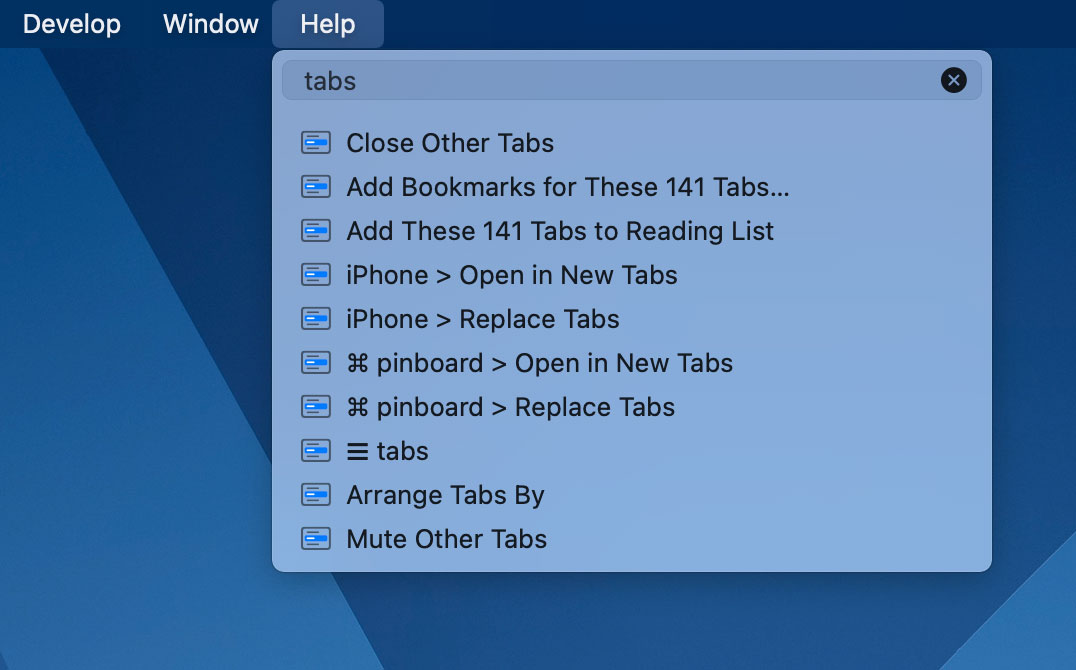

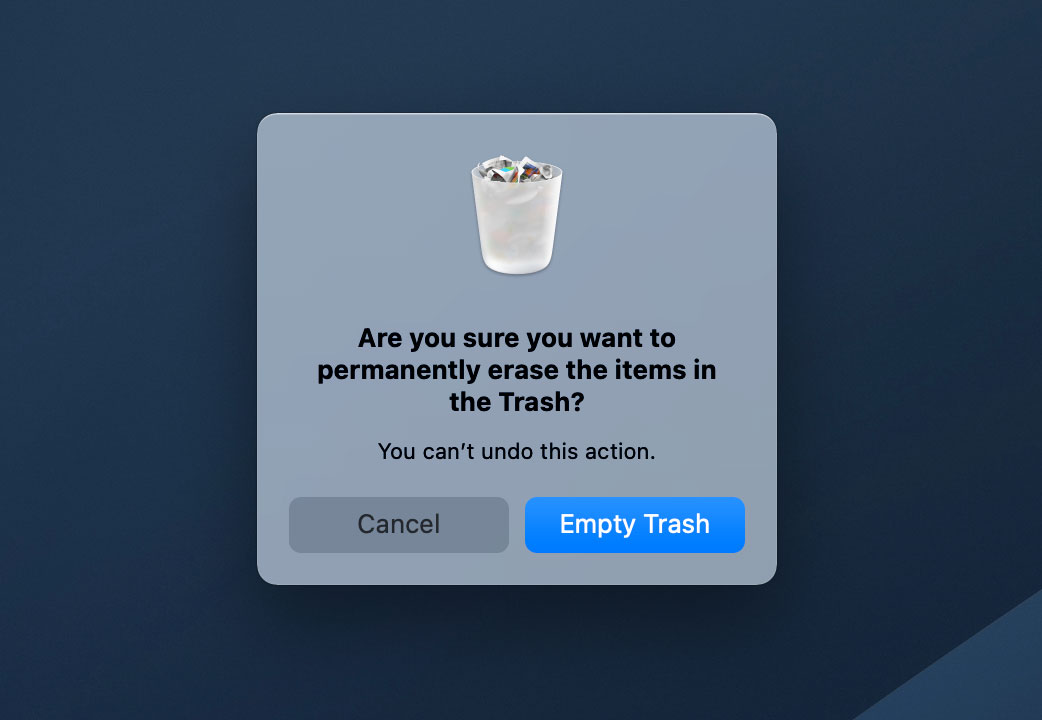

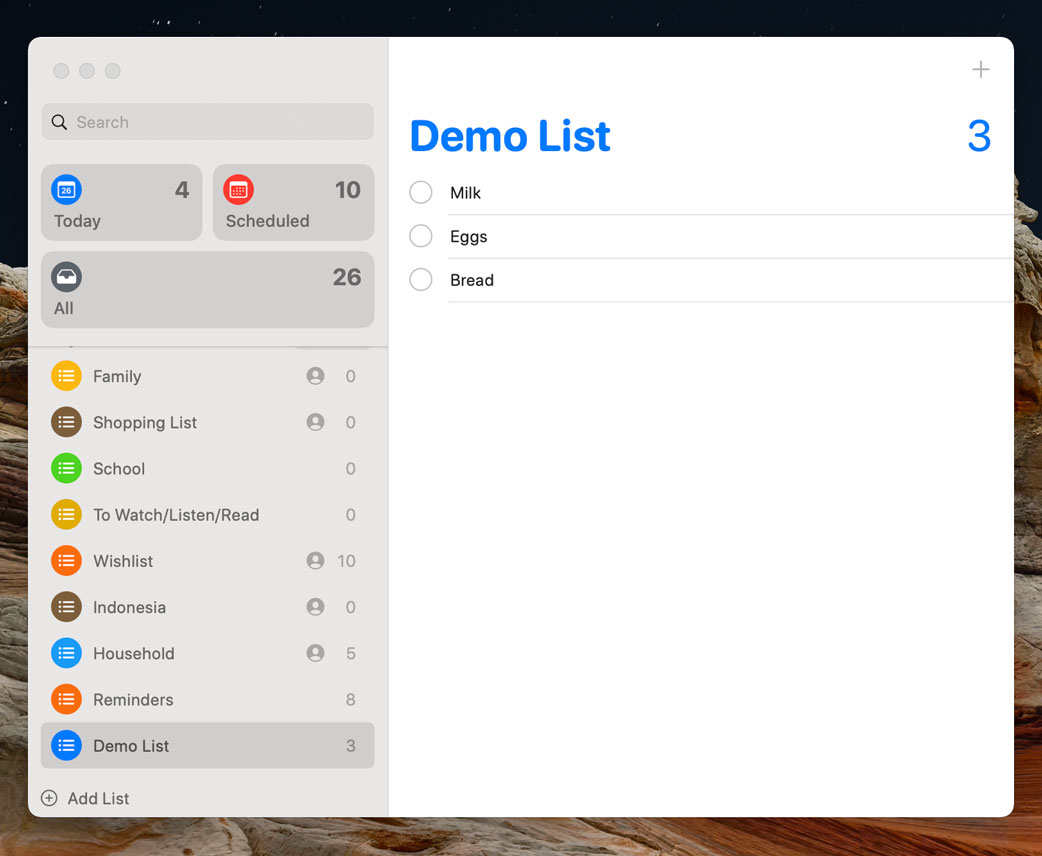

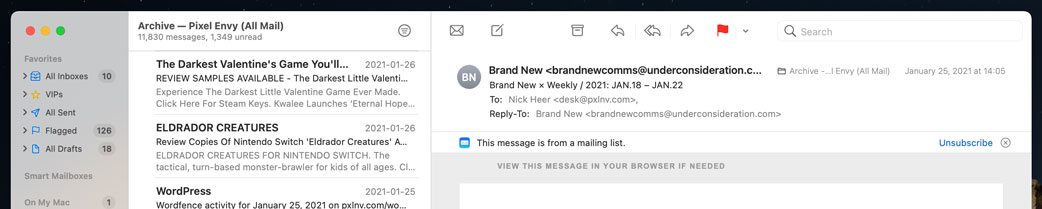

Big Sur is stable, but its redesign contains questionable choices that impair usability, some of which I strongly feel should not have shipped — to name two, notifications and the new alert style. Outside of redesign issues, I have seen new graphical glitches when editing images in Photos or using Finder’s Quick Look feature on my iMac. The Music app, while better than the one in Catalina, is slower and more buggy than iTunes used to be. There are older problems, too: with PDF rendering in Preview, with APFS containers in Finder (and Finder’s overall speed), and with data loss in Mail.

iOS 14 is much stable and without major bugs; or, at least, none that I have seen. There are animation glitches here-and-there, and I wish Siri suggestions were better.

On the other end of the scale, tvOS 14 is mediocre, some first-party apps have languished, and using Siri in any context is an experience that still ranges from lacklustre to downright shameful. I hope software quality improves in the future, particularly on the Mac. MacOS has never seemed less like it will cause a whole-system crash, but the myriad bugs introduced in the last several years have made it feel brittle.

I am now thinking I mixed up the scores for software and hardware quality. Oops.

Developer Relations: 2

An absolutely polarized year for developer relations.

On the one hand, Apple introduced a new mechanism to challenge rulings and added a program to reduce commissions to 15% for developers making less than $1 million annually. Running WWDC virtually was also a silver lining in a dark year. It’s the first WWCC I attended because hotels are thousands of dollars but my apartment has no extra cost.

On the other — oh boy, where do we begin? Apple is being sued by Epic Games along antitrust lines; Epic’s arguments are being supported by Facebook, Microsoft, and plenty of smaller developers. One can imagine ulterior motives for the plaintiff’s side, but it does not speak well for Apple’s status among developers that it is being sued. Also, there was that matter of the Hey app’s rejection just days before WWDC, and the difficulty of trying to squeeze the streaming game app model into Apple’s App Store model. Documentation still stinks, and Apple still has communication problems with developers.

Apple’s relationship with developers hit its lowest point in recent memory in 2020, but it also spurred the company to make changes. Developers should be excited to build apps for the Mac instead of relying on shitty cross-platform frameworks like Electron. They should be motivated by the jewellery-like quality of the iPhone 12 models and build apps that match in fit and finish. But I have seen enough comments this year that indicate that everyone — from one-person shops to moderate indies to big names — is worried that their app will be pulled from the store for some new interpretation of an old rule, or that Apple’s services push will raid their revenue model. There must be a better way.

Social/Societal Impact: 2

As with its developer relations, Apple’s 2020 environmental and social record sits at the extreme ends of the scale.

Apple’s response to the pandemic is commendable, from what I could see on the outside. Its store closures often outpaced restrictions from local health authorities in Canada and the U.S., but it kept retail staff on and found ways for them to work from home. It was also quick to allow corporate employees to work remotely, something it generally resists.

In a year of intensified focus on racial inequities, Apple pledged $100 million to projects intended to help right long-standing wrongs, and committed to diversity-supporting corporate practices. There is much more progress that it can make internally, particularly in leadership roles, but its recent hiring practices indicate that it is trying to do better.

Apple continues to invest in privacy and security features across its operating system and services lineup, like allowing users to decline third-party tracking in iOS apps. It also bucked another ridiculous request from the Justice Department and disabled an enterprise distribution certificate used by the creepy facial recognition company Clearview AI.

But a report at the beginning of 2020 drew a connection between discussions with the FBI and Apple’s failure to encrypt iCloud backups. It remains unclear whether one directly followed the other. Apple’s encryption policies remain confusing as far as knowing exactly which parties have access to what data. Still, Apple’s record on privacy is a high standard that its peers will never meet unless they change their business model.

China remains Apple’s biggest liability on two fronts: its supply chain, and services like the App Store and Apple TV Plus. Several reports in 2020 said that Apple was uniquely deferential to Chinese government sensitivities in its App Store policies and its original media. Many other big name companies, wary of being excluded from the Chinese market, have also faced similar accusations. But it is hard to think of one other than Apple that must balance those demands against its entire manufacturing capability. No company can be complicit in the Chinese government’s inhumane treatment of Uyghurs.

Apple is also facing increased antitrust scrutiny around the world for the way it runs the App Store, the commissions it charges third-party developers, and the way it uses private APIs.

Apple’s environmental record is less of a mixed bag. It is recycling more of the materials used in its products, new iPhones come in much smaller boxes containing nearly no plastic. Apple also says that its own operations are entirely carbon neutral, and says that its supply chain will follow by 2030.

For environmental reasons, many new products no longer ship with AC adapters in the box, and to prove it wasn’t screwing around, Apple made Lisa Jackson announce this while standing on the roof of its headquarters. Reactions to this change were predictably mixed, but it seems plausible that this has a big impact at Apple’s scale. I’m still not convinced that it makes sense to sell its charging mat without one.

Apple still isn’t keen on third-party repairs of its products, but it expanded its independent repair shop program to allow servicing of Macs.

If this were two separate categories, I think Apple’s environmental record is a 4/5 and its social record is a 2/5 — at best. I am not averaging those grades because I see liabilities with China and antitrust to be too significant.

Closing Remarks

As I wrote at the top, 2020 was a standout year in Apple’s history — even without considering the many obstacles created by this ongoing pandemic. As my workflow is dependent on these products and services, I appreciate the hard work that has gone into improving their features, but I am even happier that everything I use is, on the whole, more reliable.

What the heck is up with the Apple TV, though?