I have many thoughts about the redesigned elements common across most of Apple’s platforms but they are still brewing, much as I hope the same is true for the visual interface itself. There is one thing, though, which is a downright shame: Apple’s guidance for the shape of Mac app icons:

An app icon’s shape varies based on a platform’s visual language. In iOS, iPadOS, and macOS, icons are square, and the system applies masking to produce rounded corners that precisely match the curvature of other rounded interface elements throughout the system and the bezel of the physical device itself. In tvOS, icons are rectangular, also with concentric edges. In visionOS and watchOS, icons are square and the system applies circular masking.

This is no longer optional, but mandated by the system. App icons across Apple’s three most popular operating systems share a similar rounded square mask, and it is a downgrade. Simon B. Støvring correctly calls out the “expressive, varied app icons, a case of character over conformity” as a highlight of past versions of MacOS. I miss detailed and artistic app icons plenty. Indulging in realistic textures and thoughtful rendering was not only a differentiator for the Mac; it also conveyed the sense an app was built with a high degree of care.

Perhaps that is largely a product of nostalgia. Change can be uncomfortable, but it could be for good reasons. Stripping icons of their detail might not be bad, just different. But wrapping everything in a uniform shape? That is, dare I say, an objective degradation.

Since MacOS Big Sur debuted the precursor to this format, I have found it harder to differentiate between applications which, as I understand it, is the very function and purpose of an icon. I know this has been a long-running gripe for those of us of a certain age, but it remains true, and a walk through the history of Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines indicates the company also understands it to be true.

The uniform rounded rectangular icons in MacOS Tahoe are the product of a slow but steady series of changes Apple has made to its guidance beginning with OS X Yosemite. At its introduction at WWDC 2014, Craig Federighi said those icons were “beautifully crafted”, “so clean and yet so fundamentally still Mac”. While Apple has long provided recommendations for icon shapes and the angle at which objects should sit, its Yosemite guidelines tended to converge around specific shapes. However, Apple still advised “giving your app icon a realistic, unique shape”, since a “unique outline focuses attention on the depicted object and makes it easier for users to recognize the icon at a glance”. It also said developers should not use the same icon as a companion iOS app, since “you don’t want to imply that your app isn’t tailored for the OS X environment”.

By the next major redesign in MacOS Big Sur, Apple was extolling the “harmonious user experience” of “a common set of visual attributes, including the rounded-rectangle shape, front-facing perspective, level position, and uniform drop shadow”. Still, it emphasized the delight of including a “familiar tool” and “realistic objects” in an icon, in a manner that “float[s] just above the background and extend[s] slightly past the icon boundaries”. This is one of the reasons the MarsEdit icon remains so distinctive to me — not only does the rocket ship have enough contrast with the background, its silhouette is not the same as the icons for Mimestream above it or Fantastical below it. This is not a knock against either of those two apps; they are understandably following the documentation Apple provides and follows with all the first-party app icons I also keep in my dock.

MacOS Tahoe overrides all this previous guidance in both written policy and technical implementation. Apple, as quoted above, now says icons should be square, and the system will take care of rounding the corners — just like on iOS. Since iOS apps can run on MacOS, a lack of being “tailored for the [MacOS] environment” is no longer seen by Apple as something to caution against. But it goes further. Designers should, in its words, “embrace simplicity”:

An icon with fine visual features might look busy when rendered with system-provided shadows and highlights, and details may be hard to discern at smaller sizes. […]

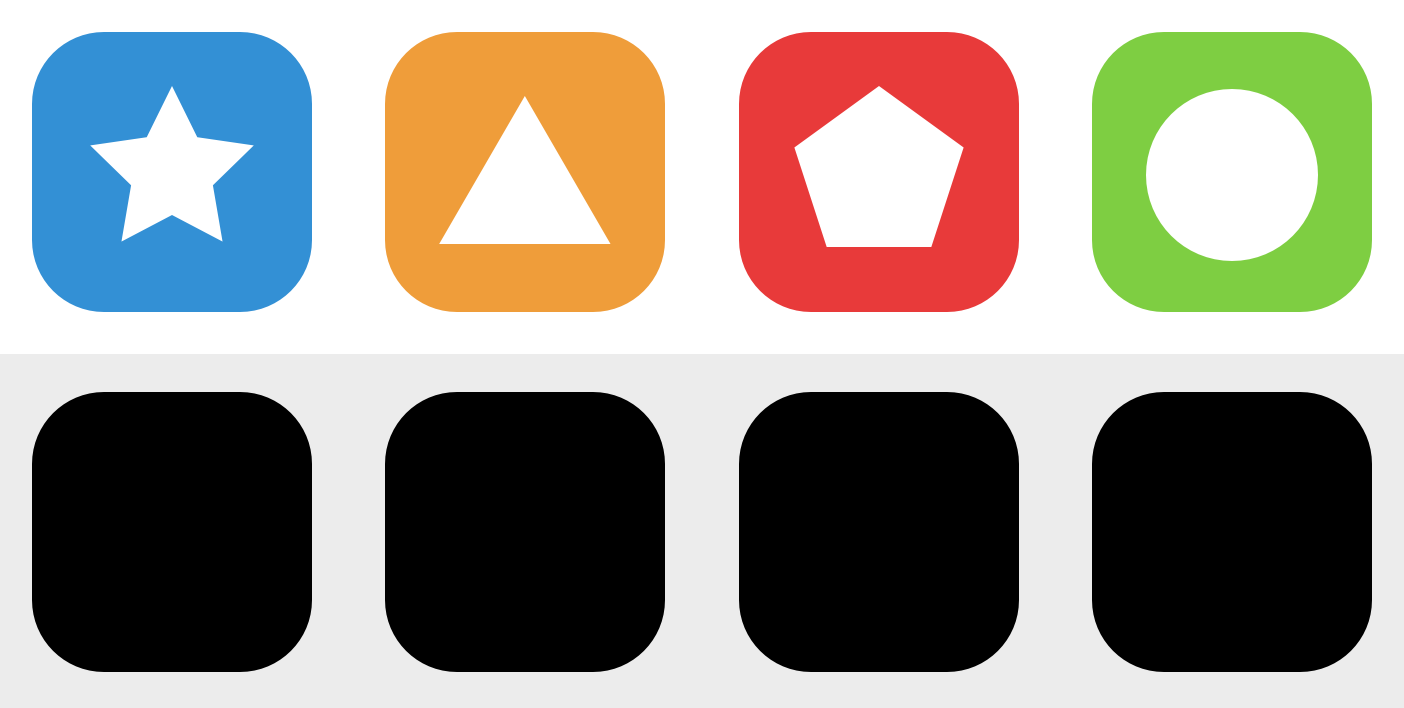

Designers no longer get to decide highlights and shadows, the system does. It defines the shape, too, and non-updated icons that do not conform are doomed to live out their days in a little grey jail cell.

Apple used to guide designers on how to make smaller icons by removing details and simplifying. Something you will often hear from designers is the fun and challenge of very small icons; how does one convey the same impression of fidelity when you have exactly 256 pixels to use? It is a delicate feat. Now, Apple simply says no icon — no matter how large — is deserving of detail. This, to me, betrays a lack of trust in the third-party designers it apparently celebrates.

Moreover, it fundamentally contradicts longstanding icon design principles. Reducing each application’s visual identity to a simple glyph — albeit with the potential for a few layers — on a coloured background necessarily leads to this perverse revision of Figure 5–15 from the 2004 Human Interface Guidelines:

Though this description and figure is specifically regarding toolbar icons, Apple’s rationale for using different shapes remains clear-eyed and simply expressed:

Each toolbar icon should be easily and quickly distinguishable from the other items in the toolbar. Toolbar icons emphasize their outline form, rather than subtler visual details.

Perhaps this reasoning is incorrect. If so, the current guidelines make no effort to explain how or why users are not guided by outline in addition to colour and enclosed shape. Apple simply says icons should be constructed “in a simple, unique way with a minimal number of shapes” on “a simple background, such as a solid colour or gradient”. Not only are there no longer any “subtler visual details”, there is also no distinct outline for each icon. I believe limitations spur creativity, but imposed uniformity sure makes that difficult. This is, however, apparently required because of new icon formats available to users, including a clear version that makes it look as though the glyph and base are an ice sculpture: cool, but entirely indistinguishable from others surrounding it. Again, this wrests control away from designers to give a little bit to users, but only at the behest of and within the boundaries of Apple’s mandates.

The technical and feature improvements in MacOS Tahoe are intriguing. I sure hope the Spotlight improvements are as excellent as they seem to be since I expect I will be increasingly dependent upon it as an application launcher. I am also excited to try Liquid Glass on a Mac. Though I remain skeptical, it is at least interesting. That is something I find difficult to see in the new direction of MacOS icons.