By pretty much any measure, iMessage is an unmitigated and hardly-celebrated success. It is a proprietary, encrypted, synchronized messaging protocol that requires virtually no configuration. It can be pseudonymous or effectively anonymous. It supports multiple media types — text, of course, but also photo, audio, video, web links, Animoji/Memoji, digital touch, Tapbacks, and so on. Despite this rich feature set, it works alongside the universal SMS standard, and most of its extended functionality gracefully falls back to SMS requirements where applicable. There is simply nothing like it in any other app or on any other platform.

The impressive thing about these add-ons is how little they’ve changed the fundamental app. If you want to use all of these extended features, they’re there; if you don’t, it’s the same Messages app you’re used to.

But as much as I appreciate how unobtrusive the additions to Messages are, their hidden nature makes them less discoverable than they could be. Message effects, for example, are hidden behind a long-press of the send button. Nobody is going to stumble into that accidentally; nobody is going to think to even do that. I see the wisdom in not wishing to make the platform’s most-used app any more complicated than it needs to be, but many of these features are borderline inaccessible. They’re also not updated very often — new Animoji characters only appear with the occasional iOS update, and message effects haven’t been altered in a few years.

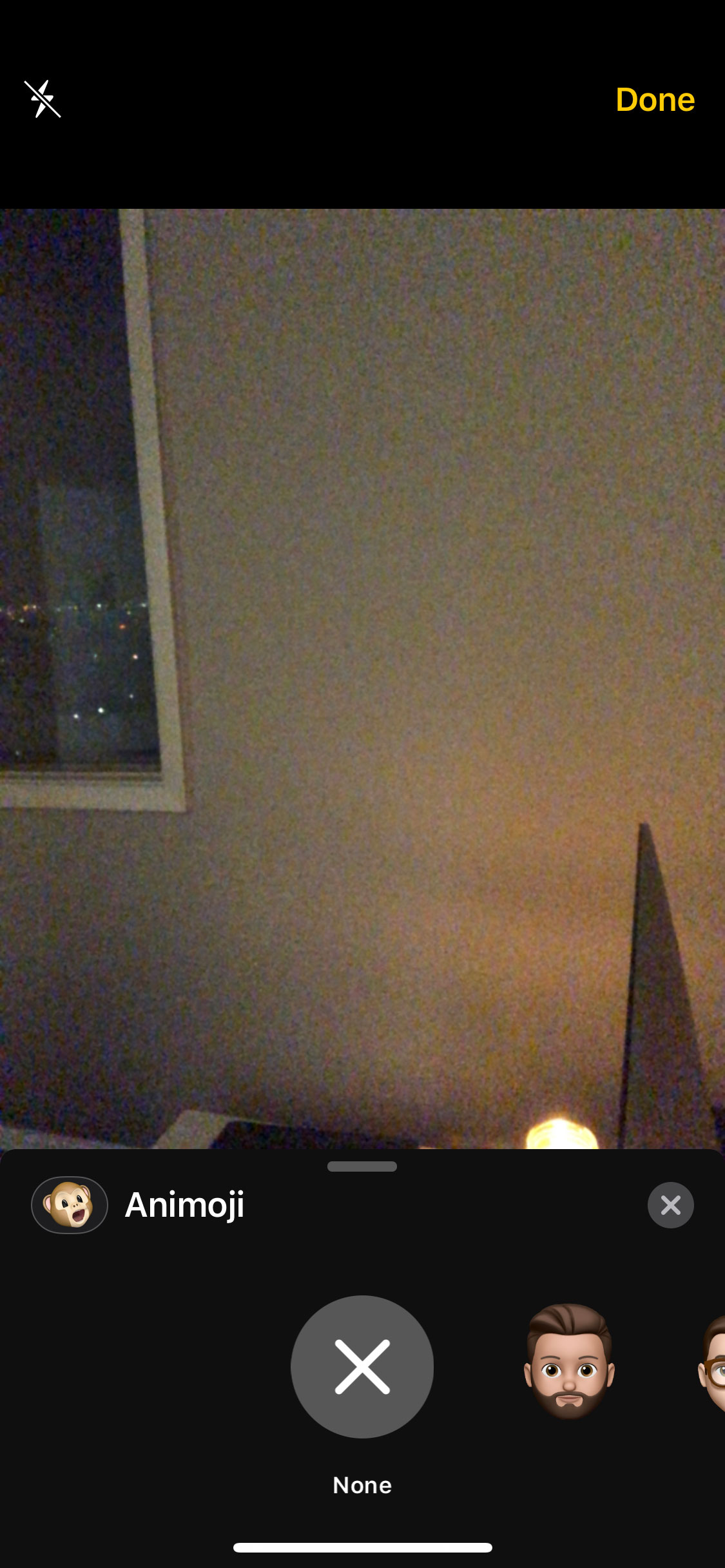

My personal bugaboo is the photo effects feature. Introduced in iOS 12, photo effects work kind of like Snapchat lenses or Instagram Stories. You can transform your selfie with the addition of Animoji or Memoji characters, add filters, and layer on text and stickers from other iMessage apps. There’s a lot to like about this feature, but it’s mired in an inscrutable and visually heavy user interface.

Let me walk you through this. You start by tapping the camera icon from within a message thread; even if you’re adding an Animoji to a photo of yourself, you cannot launch this from within the Animoji iMessage app. Then, tap the star or pentagram icon in the lower-left to start adding effects. This button does not appear anywhere else in the system,1 so your ability to figure out what it does rests entirely on your having known about it previously. Effects are added by scrolling horizontally through the app drawer at the bottom, and are applied by opening an app, selecting an effect, and then tapping the × button to close the panel. Tapping “Done” in the upper-right will, counterintuitively, dismiss the entire camera view.

This is a mess.

And, when you consider Apple’s history with this kind of thing, it’s a surprising miss. Apple has been popping cameras into the display bezels of Macs since 2005; ten years ago, you couldn’t scroll through a Facebook news feed without seeing Photo Booth pictures from your friends. That’s been replaced on every platform by postings of one smartphone photo after another — no surprise, since the total number of smartphone users worldwide far exceeds the number of traditional computer users, let alone the number of Mac users. But, even though many of those pictures may come from iPhones, virtually none of them take advantage of Apple’s photo effects because those effects are only available in Messages.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I don’t understand why, when Apple shipped the first iPhone with a front-facing camera in 2010, they did not include a Photo Booth-like app.

To be clear, I do not think it’s particularly important for Apple to chase popularity of its own apps in public social networks. The fact that Apple’s Clips app is, as of writing, the one hundred and twenty-fourth most popular app in the Photo & Video category in the Canadian App Store right now — just barely above Flickr’s app and less popular than Canon’s Connect app — is, I think, immaterial to Apple’s overall strategy. Even so, placing photo effects solely in Messages behind several layers of obfuscation and user interface weight is a bizarre choice. I feel the same way for message effects, many of the features of iMessage apps, and even Tapbacks.

I’m not advocating for a radical redesign of Messages; I’m not even convinced it’s critical for Messages itself to be redone. But I do want to feel some confidence that these features are somehow important or interesting to Apple because I find them interesting and important. They feature Memoji on billboards, but make it hard to use or even find for an average user. That is completely unlike the seamless and easy core features of Messages. I think that confusion only adds to my feelings that these extended features are needlessly complex.

The thing I keep returning to as I write this is the core beauty of Messages: its simplicity. Among the things that are most notable about these extended features is how they don’t complicate the core functionality of Messages; it only becomes a more complicated app if you figure out how to make it so. Under the surface, of course, it has become more complex, but that isn’t obvious; as a result, neither are these extended features obvious. Is there a way to make them more visible without impeding the clarity of Messages? I’m not sure. But, at the very least, I’d like to see some of these features broken out into less-siloed parts of iOS so that it’s easier to enjoy them outside of the context of an iMessage thread.

-

A small correction: this button also appears in FaceTime for the same purpose. I still think it’s unintelligible. Thanks to Joshua Price for pointing this out. ↥︎