In the 1970s and 1980s, in-house researchers at Exxon began to understand how crude oil and its derivatives were leading to environmental devestation. They were among the first to comprehensively connect the use of their company’s core products to the warming of the Earth, and they predicted some of the harms which would result. But their research was treated as mere suggestion by Exxon because the effects of obvious legislation would “alter profoundly the strategic direction of the energy industry”. It would be a business nightmare.

Forty years later, the world has concluded its warmest year in recorded history by starting another. Perhaps we would have been more able to act if businesses like Exxon equivocated less all these years. Instead, they publicly created confusion and minimized lawmakers’ knowledge. The continued success of their industry lay in keeping these secrets.

“The success lies in the secrecy” is a shibboleth of the private surveillance industry, as described in Byron Tau’s new book, “Means of Control”. It is easy to find parallels to my opening anecdote throughout though, to be clear, a direct comparison to human-led ecological destruction is a knowingly exaggerated metaphor. The erosion of privacy and civil liberties is horrifying in its own right, and shares key attributes: those in the industry knew what they were doing and allowed it to persist because it was lucrative and, in a post-9/11 landscape, ostensibly justified.

Tau’s byline is likely familiar to anyone interested in online privacy. For several years at the Wall Street Journal, he produced dozens of deeply reported articles about the intertwined businesses of online advertising, smartphone software, data brokers, and intelligence agencies. Tau no longer writes for the Journal, but “Means of Control” is an expansion of that earlier work and carefully arranged into a coherent set of stories.

Tau’s book, like so many others describing the current state of surveillance, begins with the terrorists attacks of September 11 2001. This was the early days, when Acxiom realized it could connect its consumer data set to flight and passport records. The U.S. government ate it up and its appetite proved insatiable. Tau documents the growth of an industry that did not exist — could not exist — before the invention of electronic transactions, targeted advertising, virtually limitless digital storage, and near-universal smartphone use. This rapid transformation occurred not only with little regulatory oversight, but with government encouragement, including through investments in startups like Dataminr, GeoIQ, PlaceIQ, and PlanetRisk.

In near-chronological order, Tau tells the stories which have defined this era. Remember when documentation released by Edward Snowden showed how data created by mobile ad networks was being used by intelligence services? Or how a group of Colorado Catholics bought up location data for outing priests who used gay-targeted dating apps? Or how a defence contractor quietly operates nContext, an adtech firm, which permits the U.S. intelligence apparatus to effectively wiretap the global digital ad market? Regarding the latter, Tau writes of a meeting he had with a source who showed him a “list of all of the advertising exchanges that America’s intelligence agencies had access to”, and who told him American adversaries were doing the exact same thing.

What impresses most about this book is not the volume of specific incidents — though it certainly delivers on that front — but the way they are all woven together into a broader narrative perhaps best summarized by Tau himself: “classified does not mean better”. That can be true for volume and variety, and it is also true for the relative ease with which it is available. Tracking someone halfway around the world no longer requires flying people in or even paying off people on the ground. Someone in a Virginia office park can just make that happen and likely so, too, can other someones in Moscow and Sydney and Pyongyang and Ottawa, all powered by data from companies based in friendly and hostile nations alike.

The tension running through Tau’s book is in the compromise I feel he attempts to strike between acknowledging the national security utility of a surveillance state while describing how the U.S. has abdicated the standards of privacy and freedom it has long claimed are foundational rights. His reporting often reads as an understandable combination of awe and disgust. The U.S. has, it seems, slid in the direction of the kinds of authoritarian states its administration routinely criticizes. But Tau is right to clarify in the book’s epilogue that the U.S. is not, for example, China, separated from the standards of the latter by “a thin membrane of laws, norms, social capital, and — perhaps most of all — a lingering culture of discomfort” with concentrated state power. However, the preceding chapters of the book show questions about power do not fully extend into the private sector, where there has long been pride in the scale and global reach of U.S. businesses but concern about their influence. Tau’s reporting shows how U.S. privacy standards have been exported worldwide. For a more pedestrian example, consider the frequent praise–complaint sandwiches of Amazon, Meta, Starbucks, and Walmart, to throw a few names out there.

Corporate self-governance is an entirely inadequate response. Just about every data broker and intermediary from Tau’s writing which I looked up promised it was “privacy-first” or used similar language. Every business insists in marketing literature it is concerned about privacy and says they ensure they are careful about how they collect and use information, and they have been doing so for decades — yet here we are. Entire industries have been built on the backs of tissue-thin user consent and a flexible definition of “privacy”.

When polled, people say they are concerned about how corporations and the government collect and use data. Still, when lawmakers mandate choices for users about their data collection preferences, the results do not appear to show a society that cares about personal privacy.

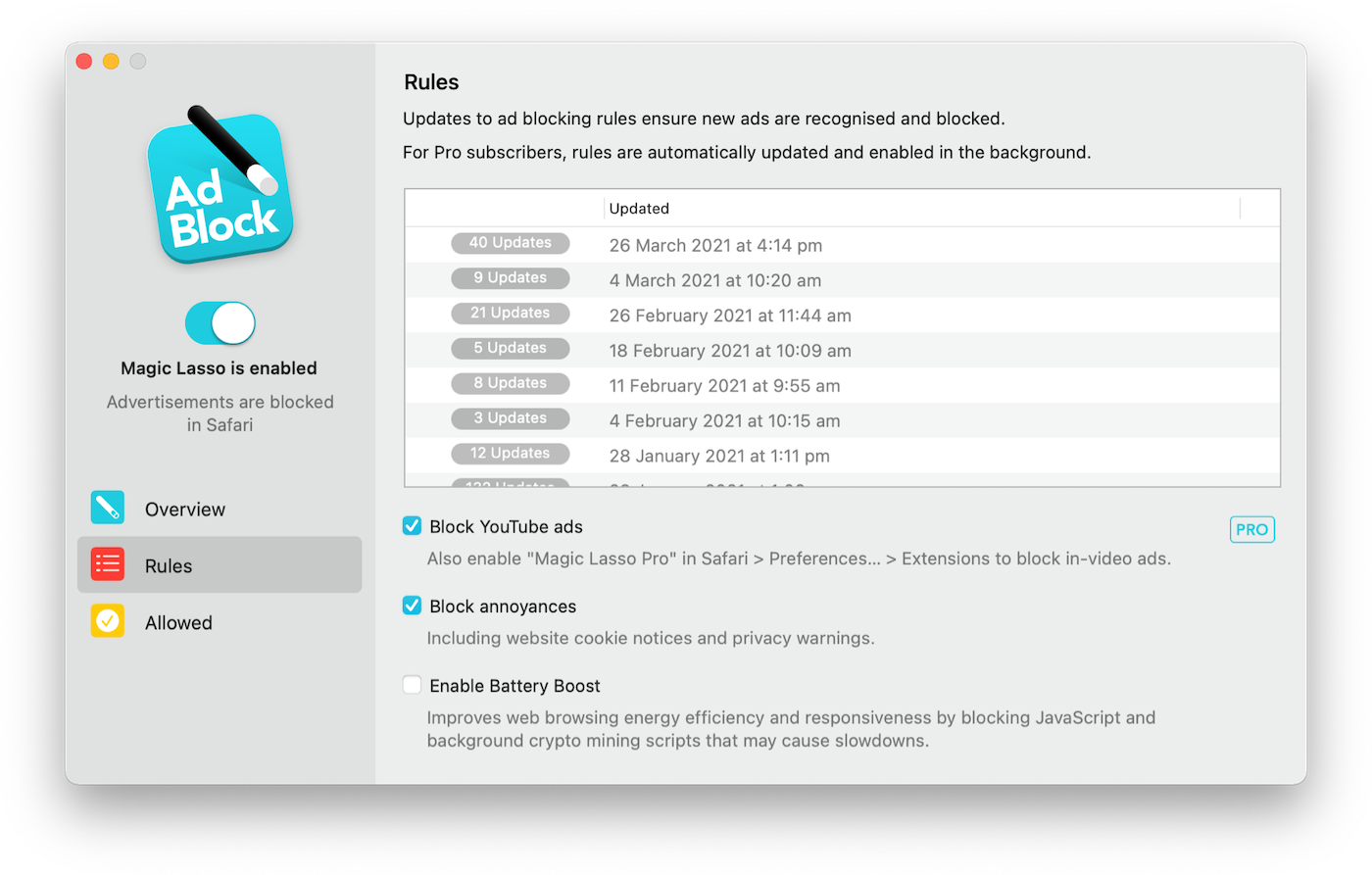

In response to the E.U.’s General Data Privacy Regulation, websites decided they wanted to continue collecting and sharing loads of data with advertisers, so they created the now-ubiquitous cookie consent sheet. The GPDR does not explicitly mandate this mechanism and many remain non-compliant with the rules and intention of the law, but they are a particularly common form of user consent. However, if you arrive at a website and it asks you whether you are okay with it sharing your personal data with hundreds of ad tech firms, are you providing meaningful consent with a single button click? Hardly.

Similarly, something like 10–40% of iOS users agree to allow apps to track them. In the E.U., the cost of opting out of Meta’s tracking will be €6–10 per month which, I assume, few people will pay.

All of these examples illustrate how inadequately we assess cost, utility, and risk. It is tempting to think of this as a personal responsibility issue akin to cigarette smoking but, as we are so often reminded, none of this data is particularly valuable in isolation — it must be aggregated in vast amounts. It is therefore much more like an environmental problem.

As with global warming, exposé after exposé after exposé is written about how our failure to act has produced extraordinary consequences. All of the technologies powering targeted advertising have enabled grotesque and pervasive surveillance as Tau documents so thoroughly. Yet these are abstract concerns compared to a fee to use Instagram, or the prospect of reading hundreds of privacy policies with a lawyer and negotiating each of them so that one may have a smidge of control over their private information.

There are technical answers to many of these concerns, and there are also policy answers. There is no reason both should not be used.

I have become increasingly convinced the best legal solution is one which creates a framework limiting the scope of data collection, restricting it to only that which is necessary to perform user-selected tasks, and preventing mass retention of bulk data. Above all, users should not be able to choose a model that puts them in obvious future peril. Many of you probably live in a society where so much is subject to consumer choice. What I wrote sounds pretty drastic, but it is not. If anything, it is substantially less radical than the status quo that permits such expansive surveillance on the basis that we “agreed” to it.

Any such policy should also be paired with something like the Fourth Amendment is Not For Sale Act in the U.S. — similar legislation is desperately needed in Canada as well — to prevent sneaky exclusions from longstanding legal principles.

Last month, Wired reported that Near Intelligence — a data broker you can read more about in Tau’s book — was able to trace dozens of individual trips to Jeffrey Epstein’s island. That could be a powerful investigative tool. It is also very strange and pretty creepy all that information was held by some random company you probably have not heard of or thought about outside stories like these. I am obviously not defending the horrendous shit Epstein and his friends did. But it is really, really weird that Near is capable of producing this data set. When interviewed by Wired, Eva Galperin, of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said “I just don’t know how many more of these stories we need to have in order to get strong privacy regulations.”

Exactly. Yet I have long been convinced an effective privacy bill could not be implemented in either the United States nor European Union, and certainly not with any degree of urgency. And, no, Matt Stoller: de facto rules on the backs of specific FTC decisions do not count. Real laws are needed. But the products and services which would be affected are too popular and too powerful. The E.U. is home to dozens of ad tech firms that promise full identity resolution. The U.S. would not want to destroy such an important economic sector, either.

Imagine my surprise when, while I was in middle of writing this review, U.S. lawmakers announced the American Privacy Rights Act (PDF). If passed, it would give individuals more control over how their information — including biological identifiers — may be collected, used, and retained. Importantly, it requires data minimization by default. It would be the most comprehensive federal privacy legislation in the U.S., and it also promises various security protections and remedies, though I think lawmakers’ promise to “prevent data from being hacked or stolen” might be a smidge unrealistic.

Such rules would more-or-less match the GDPR in setting a global privacy regime that other countries would be expected to meet, since so much of the world’s data is processed in the U.S. or otherwise under U.S. legal jurisdiction. The proposed law borrows heavily from the state-level California Consumer Privacy Act, too. My worry is that it will be treated by corporations similarly to the GDPR and CCPA by continuing to offload decision-making to users while taking advantage of a deliberate imbalance of power. Still, any progress on this front is necessary.

So, too, is it useful for anyone to help us understand how corporations and governments have jointly benefitted from privacy-hostile technologies. Tau’s “Means of Control” is one such example. You should read it. It is a deep exploration of one specific angle of how data flows from consumer software to surprising recipients. You may think you know this story, but I bet you will learn something. Even if you are not a government target — I cannot imagine I am — it is a reminder that the global private surveillance industry only functions because we all participate, however unwillingly. People get tracked based on their own devices, but also those around them. That is perhaps among the most offensive conclusions of Tau’s reporting. We have all been conscripted for any government buying this data. It only works because it is everywhere and used by everybody.

For all they have erred, democracies are not authoritarian societies. Without reporting like Tau’s, we would be unable to see what our own governments are doing and — just as important — how that differs from actual police states. As Tau writes, “in China, the state wants you to know you’re being watched. In America, the success lies in the secrecy“. Well, the secret is out. We now know what is happening despite the best efforts of an industry to keep it quiet, just like we know the Earth is heating up. Both problems massively affect our lived environment. Nobody — least of all me — would seriously compare the two. But we can say the same about each of them: now we know. We have the information. Now comes the hard part: regaining control.